M2RB: Pink Floyd

Money, it's a gas...

From Investopedia:

Some

of the countries that adopted the euro now find themselves in the position of

being unable to independently manage their monetary policy. What is being done

to establish financial stability? Essentially, new money is being pumped

into Greece and Ireland via the European Central Bank and International

Monetary Fund. This raises the question of what these actions

portend for the long-term health of the euro. History may provide some

answers.

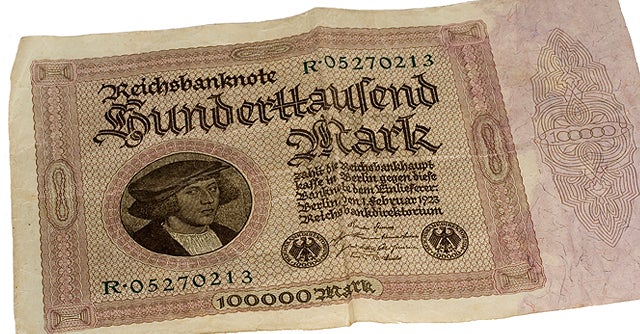

1. Papiermark (Germany)

The

Weimar Republic after World War I was the original poster child for failed

currencies. A condition of the Treaty of Versailles required Germany to

pay war reparations to the allied nations.

When Germany failed to honor the

repayments, France and Belgium occupied parts of the German industrialized

areas. This pressured the German government to print money to pay salaries

and the war debt, and hyperinflation set

in. When the Rentenmark was introduced to replace the existing currency,

the exchange rate was 1 for 1 trillion.

2. Peso (Argentina)

Argentina's economy enjoyed record

growth until the OPEC oil embargo in the mid-70s. Civil and political unrest

followed, and budget and trade deficits threatened the onset of a severe recession. Rather than reduce

spending or institute temporary borrowing to cover the shortfall, the

government resorted to printing money. A military coup in 1976 brought further

economic decline and more inflation as the money supply continued to

expand. By 1982, GDP was in freefall and dropped 12% year over year, the

worst since the Great Depression. Inflation was rampant as the

money denominations kept adding zeros until the new peso was established to

stabilize the currency. In the end, one new peso was equal to 100

billion of the original pesos (pre-1983).

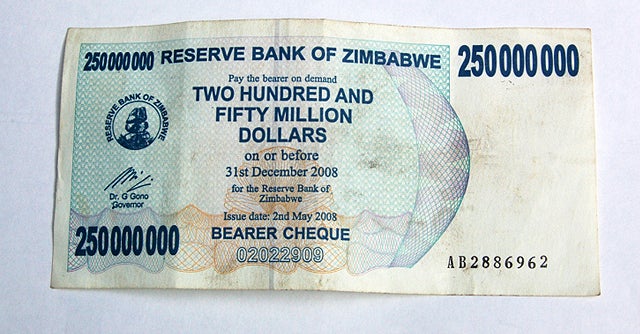

3. Dollar (Zimbabwe)

Upon gaining its independence in 1980, the

Zimbabwe dollar was valued about 25% higher than the U.S. dollar. However,

many problems led to economic decline over the next several years. The

problems were compounded by a military coup attempt that created more

instability and lack of confidence in the financial system. As

government spending escalated, wage and price controls were implemented

that produced massive budget deficits. The printing presses started

rolling and rampant inflation took hold. It reached 624% in 2004 and 1730%

in 2006. A year later, inflation zoomed to 11,000% and money was

denominated in increments of 100 million dollars. This was quickly replaced

by a 500 million dollar bill that was equivalent to about 2.5 U.S.

dollars. In 2008, the money was replaced by a new dollar that was equal to

10 billion of the old dollars.

4. Sol (Peru)

Originally an inviting target for foreign

investment, Peru embarked on a program of increased public spending in

the 1980s without a plan for dealing with the resulting

debt. Investment dried up as liberalized trade policies slowed growth and

inflation started to rise. In 1985, the government replaced the Sol with

the Inti at an exchange rate of 1,000 to 1. The largest denomination of

the new bill was 1,000 Inti note. By September 1990, monthly

inflation had reached 400% and a 10 million inti note was created to deal

with hyperinflated prices for goods and services. Only six years after

its creation, the Inti was replaced by a new version of the Sol with a

conversion rate of one billion to one.

5. Escudo (Chile)

Salvador Allende was elected president of Chile

in 1970. An avowed Marxist and

member of the Socialist Party, he nationalized industries and

dramatically increased social spending to redistribute wealth to the

poor. To pay for this, he adopted an expansive monetary policy that

initially produced economic growth, but also fueled a rise in inflation. By

the end of 1972, inflation had reached 600%. The rate had doubled to

1,200% within one year and the government defaulted on debts owed to other

countries and international banks. The Allende government was overthrown

and he committed suicide. In 1985 the Escudo was replaced by the new peso

at a 1,000 to 1 rate.

Lessons Learned

When it comes to the value and

stability of a currency, there is no free lunch. A nation's currency is

not exempt from the laws of supply and demand, so the more that is printed, the

less it is worth. While expanding the money supply may be needed in an

emergency situation, it's very difficult to reverse this policy once the emergency

has abated. As history shows, it usually takes a crisis and uncontrolled

inflation before painful steps are taken to stabilize the currency and reverse

the economic damage. (For related reading, check out The Taylor Rule: An Economic Model For Monetary Policy.)

Related:

http://tinyurl.com/az229o6

No comments:

Post a Comment