By Elliott Abrams

In 2007, early in the improbable presidential candidacy of Barack

Obama, the young first-term senator began a series of foreign-policy

speeches that seemed too general to provide a guide to what he might do

if elected. Aside from making it clear he was not George W. Bush and

would get out of Iraq, the rest read like liberal boilerplate: “We have

seen the consequences of a foreign policy based on a flawed

ideology….The conventional thinking today is just as entrenched as it

was in 2002….This is the conventional thinking that has turned against

the war, but not against the habits that got us into the war in the

first place.” In 2008, he visited Berlin and told an enraptured crowd:

“Tonight, I speak to you not as a candidate for president, but as a

citizen—a proud citizen of the United States, and a fellow citizen of

the world…the burdens of global citizenship continue to bind us

together.”

In Obama’s fifth year as president, it is increasingly clear these

vague phrases were not mere rhetoric. They did, in fact, accurately

reflect Obama’s thinking about America’s role in the world and

foreshadow the goals of the foreign policy he has been implementing and

will be pursuing for three more years. Obama’s foreign policy is

strangely self-centered, focused on himself and the United States rather

than on the conduct and needs of the nations the United States allies

with, engages with, or must confront. It is a foreign policy structured

not to influence events in Russia or China or Africa or the Middle East

but to serve as a bulwark “against the habits” of American activism and

global leadership. It was his purpose to change those habits, and to

inculcate new habits—ones in which, in every matter of foreign policy

except for the pursuit of al-Qaeda, the United States restrains itself.

I

In the beginning came

“engagement.” In his first State of the Union speech in February 2009,

Obama told us that “in words and deeds, we are showing the world that a

new era of engagement has begun.” A few days later he delivered a speech

about the Iraq war and said again that “we are launching a new era of

engagement with the world.” There would now be “comprehensive American

engagement across the region.” In his first speech to the United Nations

General Assembly, in September 2009, he repeated the phrase: “We must

embrace a new era of engagement based on mutual interests and mutual

respect….We have sought, in word and deed, a new era of engagement with

the world.”

What did the word engagement mean in this context? The message

here was that people around the world hated us for our heavy-handedness

and our militarism, which were the product not only of George W. Bush’s

policies but long-standing patterns dating back to the beginning of the

Cold War. This would now change. Our new president, the first to

recognize fully the regressive quality of activist American foreign

policy, would in the service of this goal be willing to meet even with

Iranian leaders, indeed almost any hostile dictator. The days when we

snubbed and demonized other nations were over. With Russia and other

nations there would now be a “reset”—the term that, along with

“engagement” and “global citizenship,” came to represent Obama’s foreign

policy in his first year in office.

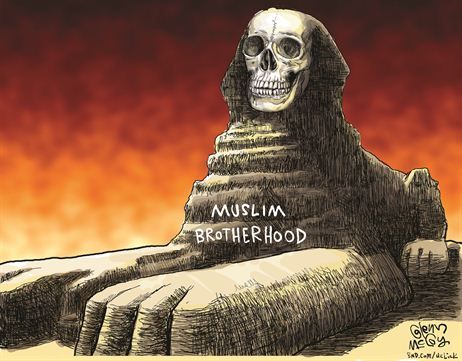

These terms applied to the world as a whole, but Obama added a

special concern with the Muslim world. Here the Bush years had, in his

view, brought near-catastrophe, and he was uniquely able to solve the

problem. “I have known Islam on three continents before coming to the

region where it was first revealed,” he remarked, and “as a boy, I spent

several years in Indonesia and heard the call of the azaan at the break

of dawn and the fall of dusk.” In his fifth month in office, he visited

Cairo not to address Egypt’s growing problems but to ignore them and

address every Muslim in the world: “I’ve come here to Cairo to seek a

new beginning between the United States and Muslims around the world,

one based on mutual interest and mutual respect….And I consider it part

of my responsibility as president of the United States to fight against

negative stereotypes of Islam wherever they appear.”

Astonishingly, he did not say he had equal responsibility when it

came to negative stereotypes of Christianity, Judaism, Buddhism,

Hinduism, or other world faiths, only Islam. Even more astonishing was

his view that American interests were best served addressing Muslims not

as Egyptians and Malaysians, or Nigerians and Omanis and Indonesians—as

residents of nations with discrete interests and goals that might

intersect with those of the United States and make us valuable friends

and allies—but as Muslims first and foremost.

This was an innovation. There was nothing new in the notion that a

president would “engage” in a different manner from the way his

predecessors had. What was new was the idea that the president of the

United States would engage directly with the followers of an entire

faith tradition. Indeed, it would appear that in his view, this new kind

of engagement—with the citizenry of the planet—was going to change

everything. Obama told the UN in his first address there: “It is my

deeply held belief that in the year 2009—more than at any point in human

history—the interests of nations and peoples are shared.” Presumably

this was a reference to his preachment in Berlin in 2008: “This is the

moment when we must come together to save this planet. Let us resolve

that we will not leave our children a world where the oceans rise and

famine spreads and terrible storms devastate our lands.”

This global citizenship we all share would, at first glance, seem to

reflect a genuine concern with how average men and women and families

are living around the world. Such a concern ought to lead to two sets of

policies: one to help them overcome political oppression, and one to

help them meet the daily challenges of poverty and disease. And here is

the second innovative aspect of Obama’s foreign policy: the startling

absence of concern on either front.

On the human-rights side, administration policy has been marked by

indifference. When the people of Iran flooded the streets to protest the

theft of their presidential election in June 2009, President Obama was

silent for 11 days. This was an early sign that “engagement” was to be

with regimes and rulers, not populations—not even, as it turned out,

with Muslim populations, and not even with Muslim populations rising up

in protest.

In an even earlier sign, when asked during a visit Mubarak made to

Washington in March 2009 about human-rights violations by his regime,

then–Secretary of State Hillary Clinton replied: “I had a wonderful time

with him this morning. I really consider President and Mrs. Mubarak to

be friends of my family.” This approach never changed: In 2011, when a

military regime replaced Mubarak, Clinton visited Cairo and said, “We

believe in aid to your military without any conditions, no

conditionality.” In 2012, she waived congressional restrictions on aid

just as the military regime was putting young American aid workers on

trial for the crime of promoting democracy in Egypt.

This was typical. Asked why she was not pressing the Chinese harder

on human rights, Secretary Clinton replied that “we pretty much know

what they are going to say” and “our pressing on those issues can’t

interfere with the global economic crisis, the global climate-change

crisis, and the security crisis.” While the Obama years have been a time

of steadily increasing oppression in Russia, the administration has

reacted with near silence. In 2009, Obama visited Moscow and told

civil-society activists that they had his “commitment” and his “promise”

to support their human-rights efforts. But after he met with Putin in

2013, Obama said the two leaders had “a very useful conversation” and

“extensive discussions about how we can further deepen our economic and

commercial relationships.” “I began by thanking him for his

cooperation,” Obama said, and he spoke about “the kind of constructive,

cooperative relationship that moves us out of the Cold War mind-set.”

Genuine support for human rights is, apparently, a “Cold War

mind-set” that leads to confrontation rather than “engagement” with

regimes. It is one of those old habits we need to break. Worse yet is

the new habit of “humanitarian intervention,” with which the Clinton and

George W. Bush administrations sometimes justified American activism.

It is apparently a cause for sadness that 100,000 people have been

killed in Syria during Obama’s tenure, in other words, but it would be

dangerous as a justification for action. Given the unsettled state of

the world, “humanitarian intervention” could lead to another bout of

military activity—precisely the kind of foreign policy Barack Obama got

himself elected to end.

So does “global citizenship” instead mean people-to-people

assistance, avoiding politics and military action to aid the millions

facing poverty and disease? Such an approach might well justify

engagement with certain regimes we would otherwise seek to isolate, and

in any event it would show deep solidarity with fellow human beings

whatever their religion, nationality, or politics. But the Obama

administration has shown no interest in such an approach. Its maligned

predecessor developed vast programs to stop the spread of malaria and

AIDS. PEPFAR (President’s Emergency Plan For AIDS Relief) had spent $18

billion by the time George W. Bush left office, and even in the view of

Bush skeptics has saved millions of lives. By contrast, Obama largely

ignored Africa during this first term, leading to news stories with

terms like “unmistakable sense of disappointment,” “widespread cynicism

on the continent,” and “positively neglectful.” If “global citizenship”

requires assisting people who are poor or sick, the key post for

advancing it in Africa is that of assistant administrator for Africa at

the Agency for International Development. Obama left that post vacant

for more than three years. Similarly, the post of ambassador-at-large

for international religious freedom was vacant for half of the

president’s first term—another indication of his interests and

priorities.

The pattern, then, is one of considerable indifference to the fate of

the poor, the persecuted, and the oppressed. They are allocated their

fair share of rhetoric, but their plight does not much impinge on

policy. Now, such an approach can theoretically be defended—as a return

to realpolitik after the excesses of the Bush administration’s “freedom

agenda” and in the face of America’s economic and fiscal crisis.

Hardhearted, perhaps, but realistic: This is the age of limits. Such

would be the defense. The problem is that a realpolitik policy would

build on American alliances to maintain and magnify American power. It

might downplay ideological or ethical matters and marginalize human

rights (wrongly, in my view), but it would do so in an effort to secure

and advance the American national interest. Is that the Obama approach?

In one area the answer is unambiguously yes, and that is the

fight against al-Qaeda terrorism. The Obama administration has vastly

expanded the use of armed drones, and concentrated a great deal of

diplomatic effort on building and maintaining alliances that share

information about terrorists, provide access to get near them, and then

strike against them. The president understands the political benefits,

of course: He and other officials have made a great deal of political

hay out of the killing of Osama bin Laden and like to say that al-Qaeda

is on the run. This works as long as there is no mass-casualty attack on

the United States attributable to al-Qaeda or a related group. But

there is no reason to doubt the sincerity the president and his team

bring to this effort. They are hard at work every day protecting

Americans from international terror.

But what other aspects of Obama’s policy appear to be dedicated to maximizing American power and national-security interests? There are none.

II

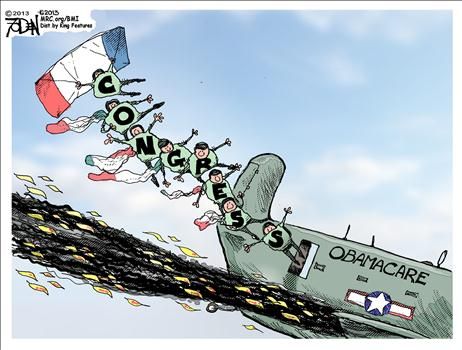

Start with American military strength, where massive cuts have left

us with a Navy of 286 ships—the smallest number since 1917. When Mitt

Romney pointed this out during a presidential debate, Obama replied

sarcastically: “Well Governor, we also have fewer horses and bayonets.

Because the nature of the military has changed.” This retort was

effective in a smart-ass way, but while the cavalry may be a historical

relic, the Navy is not, and it is getting smaller. So are the Air Force,

Army, and Marines, because their budgets are shrinking. This is not the

result of technological improvements, as Obama’s quip suggested. Nor is

it the unavoidable effect of deficits. It is a policy choice in a

Washington where entitlement spending is more sacrosanct than military

spending.

More telling, Obama avoided turning to defense when urging spending

on “shovel-ready” projects to stimulate the economy during 2009 and

2010. Due to Iraq and Afghanistan, all the services had logistical needs

that would have created tens of thousands of good jobs—building tanks

and airplanes and armored personnel carriers and jeeps, and restocking

the military’s larder. But that was not the stimulus the administration

had in mind. Meanwhile, as conventional strength declines, the

administration seeks to reduce the size of our nuclear arsenal as well,

entering negotiations with Russia while ignoring persuasive reports of

Russian cheating on the 1987 treaty limiting intermediate-range

nuclear-armed missiles. Nor is the president’s “global zero” campaign,

aimed at eliminating nuclear weapons entirely when nuclear weapons

represent a qualitative American advantage, likely to strike those who

believe foreign policy should be about maximizing American power as a

sensible program. Certainly the administration’s efforts to reduce the

size of America’s nuclear arsenal send shivers down the spines of the

South Koreans and Japanese who depend on American deterrence as they

face a rising China.

Practitioners of realpolitik would be seeking to strengthen existing

alliances, as the first Bush administration’s foreign-policy team did at

the close of the Cold War. That has not been the Obama way. In 2009,

the administration left allies in the Czech Republic and Poland high and

dry by canceling a ballistic missile defense site in Eastern Europe in

an effort to curry favor with Russia. Lech Walesa, the great

anti-Communist Polish leader, and others criticized the policy reversal

and worried about American efforts to tilt toward Moscow rather than

Warsaw and Prague. And those East European politicians who had run risks

to defend the American proposal on missile defense in 2007 and 2008

learned a painful lesson about sticking their necks out for Washington.

But closer allies have faced the same lack of respect as well. The

British learned that the bust of Winston Churchill was removed from the

Oval Office as soon as Obama arrived. Then they learned what the new

team thought of them and of the so-called special relationship. During

the visit of Prime Minister Gordon Brown in 2009, a State Department

official notoriously said: “There’s nothing special about Britain.

You’re just the same as the other 190 countries in the world. You

shouldn’t expect special treatment.”

These may have just been words, but when it came to the Western

intervention in Libya in 2011, the British and French learned that the

Obama administration’s limited view of allied solidarity posed

real-world dangers. British and French leadership finally brought all of

NATO (including the Americans, who were “leading from behind”) into the

struggle against the regime of Muammar Gaddafi, and the United States

had certain military assets that the others simply did not possess.

These were offered slowly and grudgingly and were then withdrawn as soon

as possible. The operation therefore took longer than was predicted or

was necessary: At one point the rebels appeared to have considerable

momentum and were nearing the capital, Tripoli, but they did not get the

backing they needed from the United States. Later, in April 2011, the

U.S. withdrew its warplanes, leading to advances by the Gaddafi forces.

“Your timing is exquisite,” Senator John McCain told Secretary of

Defense Gates at an oversight hearing. (Gates acknowledged the timing

was “unfortunate.”)

Then, in 2012, came Mali. Al-Qaeda-linked rebels based in the

northern part of that West African nation threatened to take over the

entire country. UN plans (supported by the United States) would have

trained and positioned African troops to combat them. But that would

happen so slowly, if it really happened at all, that these would-be

troops would present no real obstacle to the terrorist victory. France

acted, sending in troops and asking for American help in the form of

refueling the planes they were using to ferry in soldiers and police the

skies. The White House first balked at supplying the requested tankers,

then agreed to supply a few cargo planes (and asked the French to

reimburse the costs). In the end, the United States did more, because

the struggle was placed in the “counter-terror, fighting al-Qaeda”

category rather than that of mere allied solidarity (or worse yet, the

category of helping the French keep order in Africa).

This kind of drama has been playing out in Syria as well. Here, both

the strategic and humanitarian arguments for intervention are powerful.

There are now well over 100,000 dead and more than a million refugees,

in addition to several million internally displaced persons. The burdens

on Turkey and especially Jordan to cope with the refugees are growing.

The Assad regime has survived largely due to the dispatch of

expeditionary forces by Iran and Hezbollah, who are leading the fight

against the rebels. President Obama said more than two years ago that

Assad must go and called Assad’s use of chemical weapons a “red line,”

but the administration has done next to nothing to turn that threat into

reality. When justifying his decision to join the fight in Libya, Obama

said in 2011 that “when innocent people are being brutalized, when

someone like Gaddafi threatens a bloodbath that could destabilize an

entire region, and when the international community is prepared to come

together to save many thousands of lives, then it’s in our national

interest to act.” Well, in Syria, a bloodbath is a reality rather than a

threat, and the Iranian and Hezbollah intervention truly has

destabilized an entire region. But month after month, as the world

watched, Obama took no action beyond nonlethal aid to the rebels.

Finally the administration announced in June that it would provide some

military aid, but its words were not followed by deeds for several

months. Meanwhile, Sunni jihadis from around the world have been

gathering in Syria to fight the regime, creating a new threat of their

own—especially for the post-conflict period. Battle-trained, armed, and

experienced, would these jihadis stay in Syria? Or would they leave to

fight in Shia-led Iraq, against Hezbollah in Lebanon, or against Israel

in the Golan Heights? Perhaps 1,000 or 1,500 of them are European-born,

and might return to Amsterdam or London or Madrid and bring additional

violence with them.

So there are obvious realpolitik arguments for intervention in Syria,

or at the very least against the remarkable passivity of the Obama

administration there. Among those arguments is the fact that the

president has taken clear sides against Assad and has laid down his

chemical-weapons red line. His word, and American credibility, are at

stake in large measure because he chose to intervene

rhetorically. The impression left with our allies—Israeli and Arab and

European alike—is that American policy reflects less a careful weighing

of the arguments for and against action than a simple desire, visible to

them in Mali and Libya, to stay out of any military engagement that

goes beyond drone strikes.

Watching the administration in Syria, what conclusion must the rulers

of Iran reach about their own nuclear-weapons program? Must they really

abandon it? Thus far they have plowed ahead steadily. As the Economist,

a journal far closer to the realpolitik view than to neoconservative

positions, stated last summer: “Iran has installed more than 9,000 new

centrifuges in less than two years, more than doubling its enrichment

capability….Thanks to heavy investment in nuclear capacity by the

mullahs…Iran will soon be able to produce a bomb’s worth of

weapons-grade uranium in a matter of weeks.” The editors’ conclusion is

that “the balance of power between Iran and the rest of the world has

been shifting in Iran’s favour” due to its nuclear progress and to its

presence in Syria, where they urge Western intervention: “It is not in

the West’s interests that a state that sponsors terrorism and rejects

Israel’s right to exist should become the regional hegemon.” But to

Obama, a struggle against Iranian and Hezbollah soldiers seems like a

morass to stay out of at all costs. It is more important that we avoid being a “regional hegemon” than that we prevent Iran from taking that role.

As for Israel, the administration has of course followed a twisting

path since the days of Obama’s Cairo speech in 2009. On that trip he not

only skipped visiting Israel but showed no real understanding of its

history or sympathy with its situation. Military and intelligence

cooperation has been excellent, but diplomatic confrontations were

frequent, including clear evidence of Obama’s distaste for Prime

Minister Netanyahu (and vice versa). The diplomatic low point came in

early 2011, when then UN ambassador Susan Rice was forced by the White

House to veto a resolution criticizing Israeli settlements. She did as

instructed, but her explanation of her vote on behalf of the United

States could not have been more hostile: “We reject in the strongest

terms the legitimacy of continued Israeli settlement activity [which]

has corroded hopes for peace and stability in the region…violates

Israel’s international commitments, devastates trust between the

parties, and threatens the prospects for peace.”

Relations were patched up when Obama visited Israel in 2013, where

among other things he acknowledged the country’s biblical (rather than

Holocaust) roots and reiterated in tougher terms than ever before that

Iran could not be permitted to have a nuclear weapon. Whether the

Israelis credit that line and whether the ayatollahs do as well remain

the greatest questions facing Obama’s second-term foreign policy. After

Libya and Mali and Syria, after the withdrawals from Iraq and

Afghanistan, it is difficult to believe.

The overall impression in the Middle East is that America is pulling away. That Economist

editorial ended with a plea: “When Persian power is on the rise, it is

not the time to back away from the Middle East.” This is an expression

of deep anxiety, politely phrased in London but spoken with less

restraint in Jerusalem and nearly every Arab capital. In fact, the very

same words are often heard because so many Arab states—from Jordan and

Morocco to Saudi Arabia and the Emirates—have, like Israel, tied their

security to our willpower and ability to act. The prevailing mood is

trepidation. The Middle Easterners are keen students of power, and they

realize that the administration’s so-called “pivot to Asia”—the supposed

refocusing of American foreign policy away from the Middle East and

onto the Far East instead—is a weak excuse: They see that a diminishing

of the American position in their region cannot possibly help build

respect for American strength in and around China. They know that no

one, from Khamenei to Assad to Putin to Chavez, has ever seemed to fear

Barack Obama; no one has been deterred from crossing him. They watch

carefully the withdrawals from Iraq and Afghanistan, unsurprised by the

fact that the Americans are ending the wars unilaterally but studying

the terms. The administration made so little effort to work out a way to

keep a force in Iraq (through a status-of-forces agreement) that the

fair conclusion is total withdrawal was its preferred outcome. Same for

Afghanistan. In June the administration floated a new “zero option”

policy for Afghanistan: Withdraw every single American soldier next year

despite any previous pledges of support to the Afghan government. Ryan

Crocker, who was President Obama’s ambassador to Afghanistan, described

the new plan this way: “If it’s a tactic, it is mindless; if it is a

strategy, it is criminal.” The best description of Obama policy these

days seems to be “We want out.”

A former Obama administration official, Vali Nasr (now dean of the

Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies), stated all of

this most strongly in his book about the administration he served, which

he entitled The Dispensable Nation: American Foreign Policy in Retreat.

There, Nasr described America as “dragged by Europeans into ending

butchery in Libya, abandoning Afghanistan to an uncertain future, [and]

resisting a leadership role in ending the massacre of civilians in

Syria….Gone is the exuberant American desire to lead the world. In its

place there is the image of a superpower tired of the world and in

retreat.”

III

So the Obama administration is pursuing neither an idealistic foreign

policy based on altruistic considerations of “world citizenship,” nor a

realpolitik policy designed to maximize American power and influence in

an age of limits through careful assertions of power and the

strengthening and utilization of alliances. What foreign policy is it

pursuing, then?

Nasr has a theory about Obama: “His policies’ principal aim is not to

make strategic decisions but to satisfy public opinion.” This is a

damning indictment, and it is an unfair one. It is true that public

opinion wanted the American role in the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan to

end and, no doubt with those long and costly conflicts in mind, opposes a

deeper role in Syria. But public opinion does not explain the many

other stances the Obama administration has taken, from the very weak

human-rights policy and the effort to reduce the American nuclear

arsenal to the tension with Israel and the lack of support for European

allies. The argument that Obama has no real foreign-policy goals and

simply bows to the wind does not explain his actions as president. What

does?

There are two aspects to Obama’s policy. As I’ve said, the first is

the protection of the country against an al-Qaeda-linked terrorist

attack. Whether one believes this focus is motivated entirely by

patriotism or is also the product of a political calculation and fear of

public opinion is immaterial: The administration is working tirelessly,

and employing considerable violence, to attack al-Qaeda and disrupt its

plans. In pursuit of its aims it has bravely ignored the Democratic

base, which dislikes drones and electronic surveillance in general. For

four and a half years, this policy has been successful, and there is

every reason to believe it will be carried forward with equal

dedication.

The limits of this approach, however, are significant. As Thomas

Donnelly has written, “Obama was construing Bush’s ‘war on terror’ in

the narrowest possible sense: The war was a reaction to the attacks of

9/11, properly focused on Osama bin Laden and the al-Qaeda leadership

cadre, and not on the al-Qaeda network and certainly not on the overall

Middle East balance of power.” Thus the initial reluctance to help the

French in Mali despite the nature of the terrorist groups there, and the

passivity as jihadis gathered in Syria. Thus the refusal to conduct

anything like ideological warfare against Islamist extremism,

substituting instead the themes of the Cairo speech. There, Obama said,

“America is not—and never will be—at war with Islam. We will, however,

relentlessly confront violent extremists who pose a grave threat to our

security.” Absent in this phrase are the nonviolent Islamic extremists,

who are perhaps better described as the not-yet-violent Islamic

extremists. Tony Blair’s government tried the same approach and it

failed, for the British found that the key division was not between the

violent and the not-yet-violent extremists, but instead between

extremists and those who rejected extremism and hatred and were willing

to fight it. The struggle against Islamic extremism is a battle of ideas

as well as a military and police activity, and it cannot be won if the

only weapon employed is the drone strike. So one may fairly say that

fighting terrorist attacks is part of Obama’s policy, but fighting

Islamic extremism is not.

The second aspect of Obama’s foreign policy is more central and more

significant. It is the president’s effort to kill those old “habits” of

American leadership, what Nasr so well describes as “the exuberant

American desire to lead the world.” It is not enough to get out of Iraq

and Afghanistan; the lesson of Iraq and Afghanistan must also be

learned so that those mistakes are never repeated. And the lesson Obama

has learned, and wishes to teach to others, is that the exercise of

American power, with the sole exception of direct strikes on al-Qaeda

terrorists, should be avoided for practical and moral reasons.

This, I believe, is what the president was really talking about when

he said, in Berlin: “We are not only citizens of America or Germany. We

are also citizens of the world. And our fates and fortunes are linked

like never before.” He wants us to see that “exuberant desire” as

outmoded at best, and dangerous, and morally wrong.

In 2008, Obama said: “One of the things I intend to do as president

is restore America’s standing in the world. We are less respected now

than we were eight years ago or even four years ago.” Obama is not

blind; he can see that respect for us has fallen still further. He can

see that engagement with dictatorial regimes such as Iran and Syria has

failed. Relations with Russia were not “reset” and have grown worse.

There has been no improvement with China, and absolutely nothing

substantial came out of his meeting with the new Chinese premier in June

of this year. As for Iran, Obama said in 2008 that “ultimately the

measure of any effort is whether it leads to a change in Iranian

behavior.” By that standard—with Iran closer than ever to a nuclear

weapon and an Iranian expeditionary force in Syria—Obama’s Iran policy

is disastrous. America’s allies, in the Middle East, Asia, and Europe,

see a superpower that is weaker—and that continues the policies that

will make it weaker still.

Even some of Obama’s highest appointees came to see that things were

not going well and demanded bolder American action. There are press

reports that in the summer of 2012, Hillary Clinton, with the support of

then Secretary of Defense Gates, urged a far more active (covert)

effort to arm the rebels against Assad. In 2013, Clinton’s successor,

John Kerry, argued in cabinet-level secret meetings for American air

strikes at Assad’s airplanes and air bases, to shift the balance toward

the Syrian rebels and assert American power. Clinton and Gates lost;

Kerry lost; policy was unchanged; tens of thousands more Syrians died

and hundreds of thousands more fled their homes; and thousands more

jihadis arrived in Syria. With details like these in mind, one can say

that the most committed, ideological, and intransigent official in the

administration is clearly Barack Obama.

People like the Ayatollah Khamenei or Vladimir Putin are, in the

Obama view, retrogressive: They see power, defined in a very

old-fashioned manner, as the means to achieve their goals. For Obama,

national power is an improper goal. In 2013, he returned to Berlin and

this time said about people striving for freedom—he named Israelis,

Palestinians, Burmese, and Afghans—that “they too, in their own way, are

citizens of Berlin.” As Matthew Continetti wrote in the Washington Free

Beacon: “If everyone is a citizen of Berlin, then the concept of

‘citizen,’ which implies rootedness, partiality, particularity, has no

meaning. If we are citizens of everywhere, we are also citizens of

nowhere.”

Just as the British were told they were not special, so we Americans

must learn that we are not special, either—except perhaps that we are

more dangerous because we are more powerful. Thus we require more

strenuous efforts from our leaders to hold us back, as Obama is doing.

American leadership is a dangerous narcotic, one that can make us feel

good for a while but will in the end bring tragedy to us and to many

others around the world. Obama’s task is to explain this to us and,

using the powers of office, keep us away from this drug for eight years

and diminish our capacity to use it when he is gone.

This also explains the treatment of American allies such as Britain,

France, and Israel. For in this “global-citizen” view, what are allies

except people who are likely to get you into trouble? You do not plan to

intervene anywhere, so you will not need to call on them.

The danger is that they will call upon you, as happened in Mali and

Libya, and now Syria, and perhaps tomorrow Iran. Historically, America’s

closest allies were often backward in their domestic and foreign

policies, and in this view on the “wrong side of history.” What better

proof of this is there, for Obama and those who see the world as he

does, than those nations’ reliance on America and American power, and

their role throughout the Cold War as cat’s-paws for Washington?

The Obama administration appears to view allies not as nations whose

young people may someday bravely bear arms alongside ours, in the image

of World War II and Korea, but as nations likely to agree to house

secret CIA prisons. There are in this view just three sorts of nations: a

few bad actors; many dependents who may get you into trouble, and were

formerly called allies; and then of course the global citizens, who have

risen above narrow nationalist goals.

IV

Some of this is a familiar critique from the left, which rose to

influence in the 1960s and came into the White House with Jimmy Carter.

But to give the 39th president his due, the Carter Doctrine stated that

we would never permit an outside power to gain control of the Persian

Gulf. And Carter was capable of acknowledging error: In 1979, he said

the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan had “made a more dramatic change in

my opinion of what the Soviets’ ultimate goals are than anything they’ve

done in the previous time I’ve been in office.” In the Obama

administration, no action by a foreign power has elicited any such

statement of a change in perspective or approach. The president appears

to hold, unchanged, the views with which he arrived in office—and for

that matter with which he arrived in the Senate and indeed arrived at

Columbia University in 1980 (or at least with which he left Columbia

upon his graduation).

Ronald Reagan said of Jimmy Carter that his administration “lives in

the world of make-believe…where mistakes, even very big ones, have no

consequence.” Carter came to understand (briefly, in any event) that his

opinion of the Soviets had been a great mistake with whose consequences

he had to deal. But is there anything that appears to Obama to be a

mistake? Is the growing difficulty of exercising American power, is the

waning of American influence, the product of mistake—or the goal of

policy? Reagan went on in that 1980 speech to say the following: