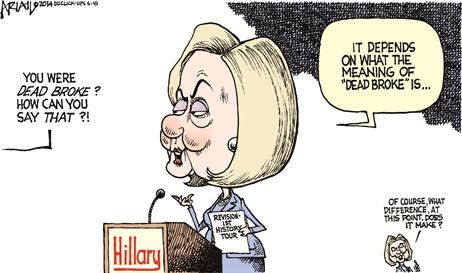

The Redskins and The Wrong Side of History

Who decides when the people need to be re-educated?

As stated by William Voegeli perfectly in the 20 January 2014 edition of The Federalist:

The

National Football League, barely a decade old and barely solvent, saw

three franchises disband before the start of the 1932 season. It added

one more, for a total of eight, when the new Boston Braves took the same

name as the major league baseball team with whom they shared a stadium,

Braves Field. Because baseball was far more popular than professional

football in the 1930s, NFL owners were not bashful about laying claim to

a bit of the brand loyalty already enjoyed by baseball franchises.

Other teams in the league that year included: the New York Giants, who

played in the Polo Grounds, home of the baseball Giants; the Brooklyn

Dodgers, who shared Ebbets Field with their baseball counterpart; and

the Chicago Bears, who played in Wrigley Field, where the Cubs played

baseball and, after a fashion, still do.

When, before the 1933 season, the football Braves relocated one mile

east to Fenway Park, the owners changed the name to the Boston Redskins,

encouraging Red Sox fans to make a connection to Fenway’s more famous

occupant while obviating changes to the logo and uniforms. According to

some accounts, the name was also an attempt to wring a marketing

advantage from the fact that the coach, Lone Star Dietz, was part Sioux,

or at least claimed to be.

The franchise remained the Redskins after relocating to Washington,

D.C., in 1937, but the future use of that name is doubtful.

Denunciations of it as an insult to American Indians reached a point

during the 2013 football season that an interviewer asked President

Obama for his position on the controversy. He replied,

cautiously, that an owner should “think about changing” a team name if

it “was offending a sizeable group of people.”

Of more importance to conservatives, columnist Charles Krauthammer

also endorsed dropping “Redskins”—not as a matter of “high principle,”

but in order to adapt to “a change in linguistic nuance.” “Simple

decency,” he wrote, recommends discarding a term that has become an

affront, even if it was used without a second thought or malicious

intent 80 years ago. A few days before Krauthammer’s column appeared, on

NBC’s “Sunday Night Football,” the highest-rated TV show throughout the

football season, studio host Bob Costas called for Washington to pick a

different team name. “‘Redskins’ can’t possibly honor a heritage or a

noble character trait,” he said, “nor can it possibly be considered a

neutral term.” Rather, it’s “an insult” and “a slur.”

[Snip]

The New Republic and Slate are among several journals

that no longer use the name in their articles. Few football fans rely

heavily on either publication, of course, but many of them read Gregg

Easterbrook’s Tuesday Morning Quarterback column on ESPN.com. By calling

the team either the “Washington R*dsk*ns” or “Potomac Drainage Basin

Indigenous Persons,” Easterbrook both observes and spoofs the growing de

facto ban on “Redskins.”

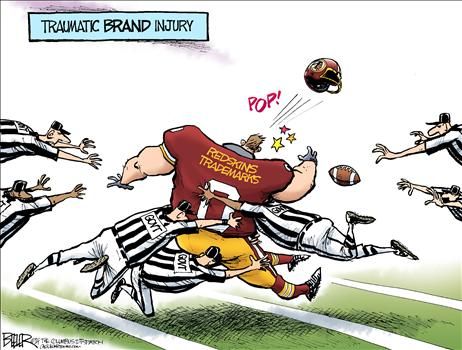

Sadly, the republic faces challenges more dire than naming a sports

team. This slight question, however, entails weightier ones about

comity—how a diverse nation coheres; discourse—how Americans address one

another; and power—not only how we make decisions, but how we decide

what needs to be decided, and who will do the deciding.

The Right Side of History

Krauthammer, Costas, and many other “Redskins” critics contend that

because sensibilities change, terminology must follow. That seems

undeniable as an abstract proposition, but doesn’t settle the question

of whether calling a professional team the Redskins in 2014 is

intolerable, either to Americans in general or American Indians in

particular. “Indian” was itself a suspect word for many years, and was

giving way to “Native American” around the time “Negro” was supplanted

by “black” or “Afro-American,” which was abandoned in favor of “African

American.” The tide receded, however. Of the 14 “National Tribal

Organizations” listed on the federal government’s website, only two use

“Native American” in their names, while 10—including the most important,

the National Congress of American Indians—use some form of “Indian.”

Apparently, a word can grow more offensive with the passage of time, but

also less offensive with the passage of additional time.

That “Redskins” is an intolerable relic from the hate-filled past,

though asserted often and strenuously, is not easily demonstrated. For

one thing, the term’s origins are neither inherently nor manifestly

derogatory. Smithsonian Institution anthropologist Ives Goddard has

traced its emergence to the 18th century, when French and English

settlers and explorers, and later Americans, adapted it from Indians,

who developed “red men” and “redskins” to differentiate themselves from

the Europeans who had come to North America.

[snip]

For another, it’s far from clear that a sizeable group of people is

offended by the name. A 2004 Annenberg poll asked 768 self-identified

American Indians, “As a Native American, do you find [“Washington

Redskins”] offensive or doesn’t it bother you?” The results were 9% and

90%, respectively. More recently, an Associated Press poll in 2013 found

that 11% of all Americans thought the team needed a different name,

compared to 79% opposed to changing it. The demographic subsets of the

polling sample yielded no data about American Indians’ views, but did

record that only 18% of “nonwhite football fans” favored getting rid of

“Redskins.”

Critics of the name who acknowledge the complexities about how it

emerged in the past and is regarded in the present make a more cautious

argument than those who declare the name tantamount to calling a team,

say, the “Washington Darkies.” In announcing Slate’s policy of

refusing to use the official name of the D.C. football team, editor

David Plotz described it as an embarrassing anachronism in an age when

“we no longer talk about groups based on their physical traits.” (Be

that as it may, Slate still refers to Americans who trace their

ancestry to Africa as “blacks,” and those descended from Europeans as

“whites.”) Thus, “while the name Redskins is only a bit offensive, it’s

extremely tacky and dated—like an old aunt who still talks about

‘colored people’ or limps her wrist to suggest someone’s gay.” (But, as

Jonah Goldberg reminded us, this daft old woman could be a donor to the

National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.)

Such arguments, then, are based less on the location than the direction of the public’s opinions and sensibilities. The New Yorker’s

Ian Crouch endorsed the views of one A.P. poll respondent: “Much

farther down the road, we’re going to look back on this and say, ‘Are

you serious? Did they really call them the Washington Redskins?’ It’s a

no-brainer.” Stipulating the constant evolution of moral standards makes

it possible to exonerate people who tolerated a problematic team name

in the past. Bob Costas, for example, had given no indication that

“Redskins” was an insult and a slur in his 39 years as a sports

broadcaster up until 2013. Prior to former owner Jack Kent Cooke’s death

in 1997, guests who watched home games with him in the owner’s box

included Al Gore, George McGovern, Earl Warren, Tip O’Neill, and Eugene

McCarthy, none of whom was criticized for endorsing a racist pageant by

their attendance. (The fact that standards evolve does not, however,

compel such exonerations. People or categories of people liberals don’t

like, such as Christian fundamentalists or whites insufficiently

committed to racial equality, are still condemned for failing to

anticipate or embrace the emerging moral strictures.)

Those who now want the Washington Redskins to be called something

newer and nicer are, it follows, “on the right side of history,” a

polemic wielded with increasing frequency. Last year the National Journal

offered a partial list of the many political positions President Obama

has declared to be on the right side of history, including support for

the Arab spring protestors, Obamacare, and immigration reform. Some of

his admirers have urged Obama to stay on the right side of history by

preventing construction of the Keystone oil pipeline. Others applauded

him for finally getting on the right side of history when, in May 2012,

he declared himself a supporter of gay marriage.

The “right side of history” is a recent addition to the lexicon, but

the idea behind it is quite old. We, in the second decade of the 21st

century, may say that the cause of the future has by now acquired a

substantial legacy from a past stretching back to the late 19th century.

Those who read the CRB and, in particular, the work of its

editor Charles Kesler, are well aware that since Progressivism appeared

on the American scene, its -ism has been that a better future beckons,

but is not simply destined. To realize it we’ll need visionary leaders

who advocate and facilitate progress. They see clearly what most see

dimly: how the future will be better than the present, and what we must do to progress from where we are to where we need to go.

In The Screwtape Letters, C.S. Lewis identified the central

contradiction of invoking tomorrow’s standards to settle today’s

controversies. Screwtape, an upper-management devil sending advisory

memoranda to an apprentice, counsels:

[God] wants men, so far as I can see, to ask very simple

questions; is it righteous? is it prudent? is it possible? Now if we can

keep men asking, “Is it in accordance with the general movement of our

time? Is it progressive or reactionary? Is it the way that History is

going?” they will neglect the relevant questions. And the questions they

do ask are, of course, unanswerable; for they do not know the

future, and what the future will be depends very largely on just those

choices which they now invoke the future to help them to make.

As journalist Michael Brendan Dougherty recently contended, “the most

bullying argument in politics” is to denounce people with whom you

disagree for being on the wrong side of history. “If your cause is just

and good, argue that it is just and good, not just inevitable.”

It’s particularly insufferable that American liberals, otherwise

boastful about their membership in the “reality-based community,” are so

facile about resorting to metaphysical mumbo-jumbo when appointing

themselves oracles of the Zeitgeist. Upon inspection, “X is on

the right side of history” turns out to be a lazy, hectoring way to

declare, “X is a good idea,” by those evading any responsibility to

prove it so. Similarly, many brandish another well-worn rhetorical club,

as when a sportswriter charges that current Redskins owner Dan Snyder

refuses to rename his team because he just doesn’t “get it.” That huffy

formulation conveniently blames someone else’s refusal to see things

your way on his cognitive or moral deficiencies, rather than on your forensic ones.

Bending Toward Justice

Things do change, of course. history, society,…life are all dynamic,

not static. The quotidian work of politics, in particular, is more

concerned with accommodating and channeling the transient than with

realizing eternal Platonic forms. “A majority,” Abraham Lincoln said in

his First Inaugural, “held in restraint by constitutional checks, and

limitations, and always changing easily, with deliberate changes of

popular opinions and sentiments, is the only true sovereign of a free

people.”

Notwithstanding the opinion polls showing a large majority untroubled

by “Washington Redskins,” there clearly has been a deliberate change

away from cartoonish, disrespectful references to Indians by sports

teams. In 1986, the Atlanta Braves baseball team (formerly the Boston

franchise, relocated by way of Milwaukee) got rid of “Chief Noc-a-Homa,”

a mascot who would emerge from a teepee beyond the left field fence to

perform a “war dance” after every Braves home run. Some major college

athletic programs have renamed their teams: the Stanford Indians became

the Cardinal; Marquette’s Warriors are now the Golden Eagles; and the

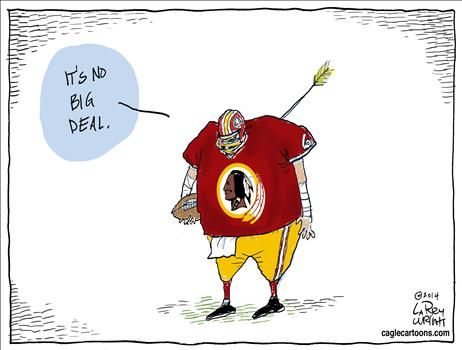

St. John’s Redmen the Red Storm. The Redskins retain their team name and

fight song, “Hail to the Redskins,” but have changed the words. Fans no

longer sing, “Scalp ’em, swamp ’em—we will take ’em big score / Read

’em, weep ’em, touchdown!—we want heap more!”

[snip]

It would be astonishing if anyone started a campaign to bring back

Chief Noc-a-Homa, or to restore the Redskins fight song’s original

lyrics, much less for such an effort to succeed. History may close no

questions, but some are exceedingly unlikely to be reopened. It’s an

unwarranted leap, however, from these developments to the judgment by

Marc Tracy, a New Republic writer, that polls showing only a

small portion of the population shares his outrage at “Washington

Redskins” are irrelevant. He claims it doesn’t matter how few people

oppose the name because it is “objectively offensive,” a judgment not

obviously true or even coherent, since taking offense would seem to be

highly subjective. The suspicion that Tracy thinks it sufficient to

demand that sensibilities like his should prevail because that’s what he

really, really wants is supported by his catalog of other athletic

teams with Indian names or logos he finds objectionable. That the

University of Utah has official permission of the Ute Nations to call

its teams the Utes, for example, does not banish Tracy’s doubts about

the seemliness of the athletic program’s logo, which shows two feathers

attached to the letter U. He considers the arrowhead in the San Diego

State Aztec’s logo even more shameful.

Being on the right side of history is about timing—but not just about

timing. There’s more to it, that is, than getting where the crowd is

headed a little before the crowd arrives, the key to making money in

equities or real estate. The right side, for progressives, is the side

they deem right, not just the thing that happens next. The causes that

deserve to win are destined to prevail because, as Martin Luther King

said in 1965, the “arc of the moral universe is long but it bends toward

justice.”

[snip]

That famous declaration, like others made in sermons, neither lends

itself to nor profits from scrutiny. For one thing, it’s

unfalsifiable—an assertion that something will eventually come to pass can always be defended on the grounds that it hasn’t come true yet.

For another, what justice means and requires is the subject of an old,

profound debate, not a standard that settles political problems the way

the definition of an isosceles triangle settles geometry problems.

King’s heavy reliance on the concept of the “beloved community” argues

that he relied on an understanding of justice for which the descriptor

“expansive” is much too narrow. “For Dr. King, The Beloved Community was

not a lofty utopian goal,” the Martin Luther King, Jr., Center for

Nonviolent Social Change states, before describing it in lofty utopian

terms as “a global vision, in which all people can share in the wealth

of the earth.” In this vision, “poverty, hunger and homelessness will

not be tolerated,” “all forms of discrimination, bigotry and prejudice

will be replaced by an all-inclusive spirit of sisterhood and

brotherhood,” and “international disputes will be resolved by peaceful

conflict-resolution and reconciliation of adversaries, instead of

military power.”

Identity Politics

That vision, suffice to say, doesn’t rule out very much, either in

terms of grievances or the measures needed to rectify them. Since King’s

death 46 years ago, it has ruled in more and more. According to the

Hoover Institution’s Tod Lindberg, the historical tide demanding ever

greater equality—the subject of Tocqueville’s Democracy in America—at

first rendered political differences untenable, resulting in government

by consent of the governed, expressed though universal suffrage. It

then found economic disparities unacceptable, which led to efforts to

reduce them with proletarian revolution, socialism, and welfare states.

It now finds social differences among various groups intolerable. In

order to “bring down the status of the privileged and elevate the status

of the denigrated,” Lindberg writes, those described by various markers

of social identity—race, sex, class, sexual orientation, ethnicity,

etc.—must all be accorded full and equal regard.

The attainment of perfect political or economic equality is highly

unlikely, but can be described intelligibly, even as it is possible for

political and economic inequalities to be objectively assessed. By

contrast, equal social status rests on subjective feelings of being

included and affirmed, rendering it as nebulous in theory as it is

elusive in practice. Although a perfectly homogenous society might

achieve absolute equality of social status, the “Tocqueville effect”

argues that increasing equality always renders remaining inequalities

all the more noticeable and suspect. As long as humans are not identical

there will be differences among them, which will give rise to real or

perceived inequalities.

In any case, the point of social equality is not to eliminate

differences but to celebrate them. The psychological strength that

follows from this achievement is the embrace, not the denial, of one’s

nature and heritage. Thus, the National Congress of American Indians

(NCAI) demands abandoning “Washington Redskins” because, when exposed to

“Indian-based names, mascots, and logos in sports,”

the self-esteem of Native youth is harmfully impacted,

their self-confidence erodes, and their sense of identity is severely

damaged. Specifically, these stereotypes affect how Native youth view

the world and their place in society, while also affecting how society

views Native peoples. This creates an inaccurate portrayal of Native

peoples and their contributions to society. Creating positive images and

role models is essential in helping Native youth more fully and fairly

establish themselves in today’s society.

The NCAI position paper, whose weakest claims echo the notorious “doll experiment” argument of 1954’s Brown v. Board of Education

decision, moves directly from these premises to discuss how Indians are

disproportionately likely to be victims of suicide and hate crimes. It

does not even attempt to establish a causal relationship between these

dire outcomes and the psychological changes it deplores. What’s more,

its social scientific argument for a cause-and-effect relationship

between Indian mascots and Native youth’s impaired self-esteem and

confidence rests entirely on a single, ten-page conference paper by an

assistant professor of psychology.

But whether the links in the empirical chain between team names and

logos, on the one hand, and depression and suicide, on the other, are

sturdy or flimsy is not really the point. Last December, Melissa

Harris-Perry, a Tulane University political science professor, found

herself attacked for a segment on the MSNBC television show she hosts.

Two days after Harris-Perry and her panelists made derisive references

to a Romney family photograph that included an adopted black grandchild

sitting on the former governor’s lap, she posted to her Twitter account,

“Without reservation or qualification…I want to immediately apologize

to the Romney family for hurting them.” She explained the basis for this

apology in the compressed locution of Twitter: “I work by guiding

principle that those who offend do not have the right to tell those they

hurt that they r wrong for hurting.”

Though explaining a great deal about life in 21st-century America,

this guiding principle offers very little guidance for navigating the

political and social terrain. Harris-Perry rules out the possibility of a

false positive: if you r hurting, you were offended. By

this illogic, claims to having been hurt and offended—or at least ones

put forward by groups formerly or presently victimized by

discrimination—are never dishonest, mistaken, or overwrought. There are

no innocent explanations because the subjective experience of having

been hurt necessarily means that the offenders are indeed guilty of

inflicting a wound. For them to protest to the contrary only compounds

the original offense, as it further denigrates the injured party by

signaling that their hurt feelings are trivial, contrived, or spurious.

Why American Indians don't mind 'Redskins'