By Kevin G. Hall — McClatchy Washington Bureau

WASHINGTON — Wondering who to

thank for the bizarre rules that allow Congress to approve spending,

then later slam the door on new borrowing to pay the bills? Thank the

Founding Fathers.

Article 1 of the U.S. Constitution grants

Congress the exclusive powers to legislate and the power of the purse.

In fact, Section 8 of the first article deals specifically with paying

debts.

But the Constitution’s Article 2 empowers the president to

carry out the laws passed by Congress and run the government at the

levels authorized and appropriated by Congress.

In that simple

civics lesson is the root of the problem. Congress passes legislation to

spend, but it’s the president who must ensure those bills get paid.

Those two objectives don’t neatly line up. President Barack Obama

complains that past presidents haven’t been subjected to the types of

conditions being asked of him in exchange for lifting the debt ceiling,

but it just isn’t true. To the contrary, there’s plenty of precedent.

“In the past, Congress has responded to make sure that the Treasury can

still keep borrowing, but debt and budgets have always been

contentious,” said D. Andrew Austin, an analyst in government finance

for the nonpartisan Congressional Research Service and the author of a

brief but thorough history of the debt limit.

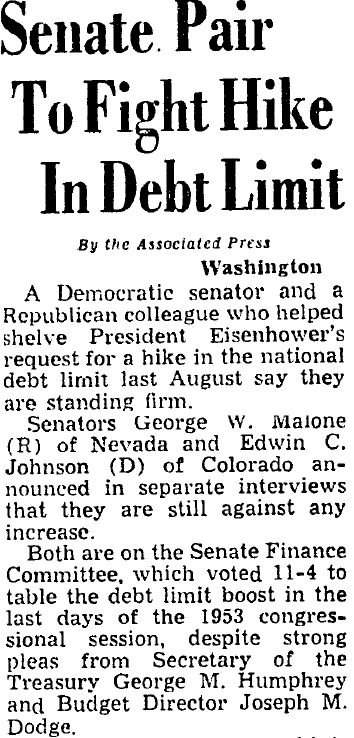

His research shows that fights over installing a new cap on the nation’s debt are hardly a new phenomenon.

“While

the debt limit has never caused the federal government to default on

its obligations, it has at times caused great inconvenience and has

added uncertainty to Treasury operations,” Austin wrote.

The

Constitution created the backdrop for fights between Congress and the

president over spending and taxes, but the actual statutory limit on

just how much debt the federal government can incur began almost 100

years ago, with the Second Liberty Bond Act of 1917.

Before then,

Congress had from time to time given the Treasury Department authority

to issue bonds to raise money for special projects. And Congress had

authorized borrowing for specific reasons such as for building the

Panama Canal.

The issuance of long-term Liberty Bonds changed the

game. They were authorized so that the federal government could better

hold down its borrowing costs as it funded America’s entry into World

War I. In 1919, the debt ceiling was about $43 billion, but at the close

of the fiscal year debt actually stood at about $25.5 billion, with

Congress reluctant to borrow all that was authorized.

Several

decades of congressionally mandated debt limits followed, and it gave

Treasury officials more autonomy to issue debt. Austin’s report notes

that at the start of World War II, the U.S. debt ceiling of $45 billion

was just 10 percent higher than the $40.4 billion in actual debt. Actual

borrowing matched up more neatly with authorized amounts. Until the

cost of World War II exploded, that is. By 1945, the debt ceiling was

set at $300 billion.

The debt ceiling actually fell, to

$270 billion, after the war and stayed there until about 1954. The

Korean War was paid for through higher taxes, not more debt. And between

1954 and 1962, the debt limit fell twice and increased seven times. It

didn’t return to the World War II high-water mark again until March

1962.

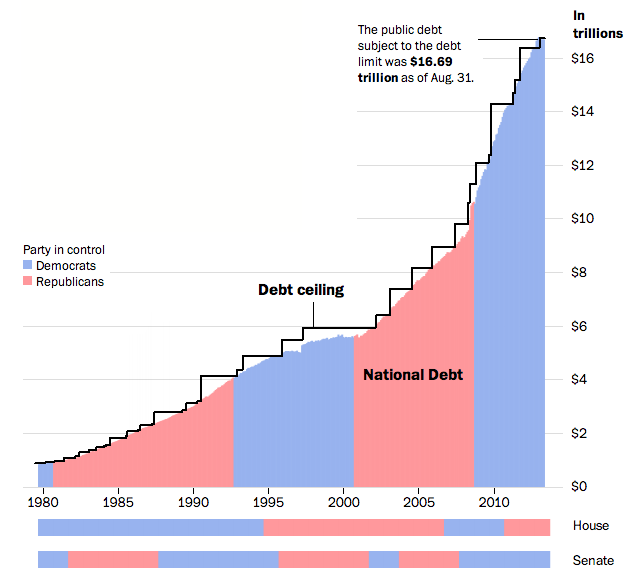

From

that point forward, there were 69 changes to the debt limit through the

end of the 2007-2008 fiscal year, including the largest single-chunk

increase, $984 billion in May 2003, as America borrowed to pay for wars

in Afghanistan and Iraq while also cutting taxes.*

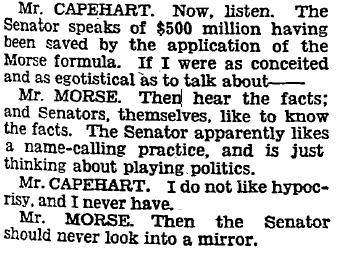

During

the 1980s and early 1990s, there was brief respite from the

politicization of the U.S. debt ceiling. Lawmakers had grown tired of

passing spending increases and then voting against raising the debt

ceiling for their profligate spending. It made them appear hypocritical

in front of the voters, and that second vote to allow more borrowing

never played well back home.

In 1979, up-and-coming

Missouri Democrat Dick Gephardt, who later became House majority leader,

won a parliamentary ruling that allowed any final vote on a budget to

automatically raise the debt ceiling.

The so-called Gephardt Rule

was welcomed by both major political parties because it eliminated the

need to take that separate and politically costly vote to raise the debt

ceiling. Over time, it lost its luster because senators amended the

budget passed by the House, meaning it had to come back to the House for

another vote, which had the same effect as voting to raise the debt

ceiling.

The Gephardt Rule, however, ended when Republicans took

back the House of Representatives in the 104th Congress and in 1995

Georgia Republican Newt Gingrich became House speaker. He saw an

opportunity to use the debt ceiling for political leverage.

“It

was looked at by conservatives as another opportunity to take a whack at

the fiscal situation . . . since the Senate was historically amending

the debt limit,” said William Hoagland, a former Republican staff

director for the Senate Budget Committee.

Since the demise

of the Gephardt Rule, whichever political party controlled the Congress

has generally used the debt ceiling as a political tool, returning to

the 1970s practice of increasing spending but also voting against

raising the debt ceiling.

In one example, Sen. Barack Obama took

to the Senate floor on March 16, 2006, in opposition to raising the debt

ceiling while George W. Bush was president.

“Increasing America’s debt weakens us,” Obama argued then.

That month, China held $635.4 billion in U.S. government debt. By this July, that number had doubled to nearly $1.28 trillion.

Some

experts actually see value in the frequent fights over raising the debt

ceiling, because they force the two major parties to bridge divides.

“In

fact, debt limit increase bills have served not only as vehicles for

bipartisan fiscal reform measures, but catalysts for subsequent

negotiations about debt reduction,” wrote Anita Krishnakumar in the 2005

edition of the Harvard Journal of Legislation.

“Upon careful evaluation, it is clear that the statute retains enduring value.”

* Not quite...

From the Congressional Research Service:

On 02.17.09, the debt ceiling was increased by $789 billion (P.L. 111-5) from $11.315 trillion to $12.104 trillion.

On 12.28.09, the debt ceiling was increased by $290 billion (P.L. 111-123).

On 02.12.10, the debt ceiling was increased by $1.9 trillion (P.L. 111-139).

On 2 August 2011, President Obama signed the Budget Control Act of 2011 into law, which increased the debt ceiling by $2.1 - $2.4 trillion in three stages. Upon his signature, the debt ceiling was increased by $400 billion. The second tranche of $500 billion was triggered on 22 September 2011. On 01.12.12, presidential certification triggered a third, $1.2 trillion increase on 28 January 2012.

Federal debt reached its limit on 12.31.12. 'Extraordinary measures' were estimated to allow payment of government obligations until mid-February or early March 2013. H.R. 325, which suspended the debt limit until 19 May 2013, was passed by the House on 01.23.12 and by the Senate on 01.31.13. Obama signed it into law on 02.04.13.

According to the White House Office of Management and Budget, those 'extraordinary measures' amount to about $550 billion, which means that $6.7 trillion has been added to the national debt under the Obama presidency and we now have an estimated $17.25 trillion national debt.

For those keeping score at home, that adds up to $5.929 trillion in debt ceiling increases and 'extraordinary measures' on Obama's watch, which has lasted 4 years, 8 months, and 15 days so far.

Under BOOOOOOOOOOOOOSH?

Per the CRS:

06.28.02: $450 billion (P.L. 107-199)

05.27.03: $984 billion (P.L. 108-24)

11.19.04: $800 billion (P.L. 108-415)

03.20.06: $781 billion (P.L. 109-182)

09.27.07: $850 billion (P.L. 110-91)

07.30.08: $800 billion (P.L. 110-289)

10.03.08: $700 billion (P.L. 110-343)

That totals to $5.365 trillion in debt ceiling increases over a span of 8 years.

Again, Obama has increased the debt ceiling by $5.929 trillion in 4 years, 8 months, and 15 days.

But, you see, according to JustTheЯ3t@rD, $5.929 trillion is 1/3rd of $5.365 trillion or something.

http://tinyurl.com/oqv8alw