"Don't panic about the sequester...The USA has an 'infinite amount of money.'"

- Mayor Michael Bloomberg, 1 March 2013

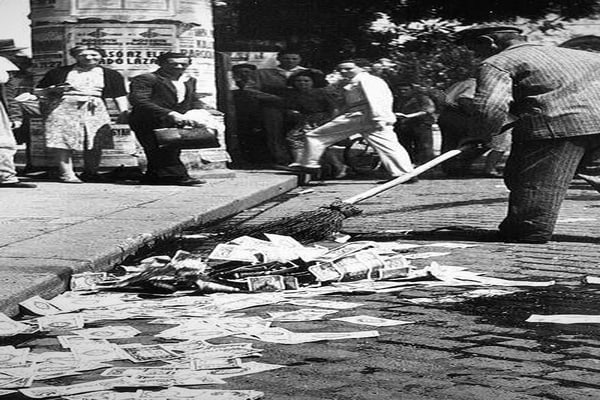

In October 1923, the monthly inflation rate hit 29,500%, according to the Cato Journal. In December 1923, 4.2 trillion marks would get you one US $1.

In July 1946, the monthly inflation rate was 4.19 x 1016% and the daily inflation rate was 207%.

In December 2008, Zimbabwe's inflation rate was 516 quintillion percent and prices doubled every 1.3 days.

In 1973, Chile's hyperinflation rate hit 700%,

at a time when the country, under high protectionist barriers, had no foreign reserves, and GDP was falling.

Argentina's inflation rate was 12,000%.

In January 1994, the official monthly inflation rate was 313

million% — 4 orders of magnitude higher than the Weimar hyperinflation rate.

In 1987, the annual inflation rate hit 30,000% in Nicaragua.

Between May and August 1985 - it's peak - Bolivia's inflation rate rose to 60,000% on an annualised basis.

From CNBC: The Worst Hyperinflation Situations of All Time

#1: Hungary 1946

Highest monthly inflation: 13,600,000,000,000,000%

Prices doubled every: 15.6 hours

The

worst case of hyperinflation ever recorded occurred in Hungary in the

first half of 1946. By the midpoint of the year, Hungary's highest

denomination bill was the 100,000,000,000,000,000,000 (One Hundred

Quintillion) pengo, compared to 1944s highest denomination, 1,000 pengo.

At the height of Hungary's inflation, the CATO study estimates that the

daily inflation rate stood at 195 percent, with prices doubling

approximately every 15.6 hours, coming out to a monthly inflation rate

of 13.6 quadrillion percent.

The situation was so dire that the government adopted a special currency that was created explicitly for tax and postal payments and was adjusted each day via radio. The pengo was eventually replaced later that year in a currency revaluation, but it is estimated that when the currency was replaced in August 1946, the total of all Hungarian banknotes in circulation equaled the value of one one-thousandth of a US Dollar.

The situation was so dire that the government adopted a special currency that was created explicitly for tax and postal payments and was adjusted each day via radio. The pengo was eventually replaced later that year in a currency revaluation, but it is estimated that when the currency was replaced in August 1946, the total of all Hungarian banknotes in circulation equaled the value of one one-thousandth of a US Dollar.

Causes of Hungary's 1946 Inflation

The Hungarian pengo was first introduced in

the wake of the first World War in order to stabilize the country's

economy and correct the country's inflation.

Hungary's agricultural sector was hit especially hard by the Great Depression, and the country's mounting debt forced the central bank to devalue the currency to cover costs by loosening financial and monetary policy. Later in the decade, the Vienna Awards ceded Hungary territories that it claimed were lost during World War I, but these lands were economically underdeveloped and eventually caused a strain on the national economy.

When World War II hit, Hungary was in a weak economic position and the central bank was almost entirely under the government's control; printing money based on the government's budgetary needs without any sort of financial restraint.

Eventually, the inflationary environment became so dire that coins began disappearing form circulation, beginning with the silver coins and even bronze and nickel currency, as the component metals became far more valuable than the coins themselves. As the war wound down, the standing government took full control of banknote production without any tangible collateral, and the occupying Soviet army simultaneously began issuing its own military money, which further reduced the demand for the pengo.

Hungary's worst hyperinflation occurred after World War II, and despite several large-scale measures to stabilize the currency, the only remedy was to introduce a new currency, the forint, which had a direct conversion into gold and thus into other world currencies. The forint is still in circulation today, but it is expected to be replaced by the euro within the next several years.

Hungary's agricultural sector was hit especially hard by the Great Depression, and the country's mounting debt forced the central bank to devalue the currency to cover costs by loosening financial and monetary policy. Later in the decade, the Vienna Awards ceded Hungary territories that it claimed were lost during World War I, but these lands were economically underdeveloped and eventually caused a strain on the national economy.

When World War II hit, Hungary was in a weak economic position and the central bank was almost entirely under the government's control; printing money based on the government's budgetary needs without any sort of financial restraint.

Eventually, the inflationary environment became so dire that coins began disappearing form circulation, beginning with the silver coins and even bronze and nickel currency, as the component metals became far more valuable than the coins themselves. As the war wound down, the standing government took full control of banknote production without any tangible collateral, and the occupying Soviet army simultaneously began issuing its own military money, which further reduced the demand for the pengo.

Hungary's worst hyperinflation occurred after World War II, and despite several large-scale measures to stabilize the currency, the only remedy was to introduce a new currency, the forint, which had a direct conversion into gold and thus into other world currencies. The forint is still in circulation today, but it is expected to be replaced by the euro within the next several years.

#2: Zimbabwe, November 2008

Highest monthly inflation: 79,600,000,000%

Prices doubled every: 24.7 hours

The

most recent example of hyperinflation, Zimbabwe's currency woes hit a

peak in November 2008, reaching a monthly inflation rate of

approximately 79 billion percent, according to the Cato Institute.

Although the Zimbabwean government stopped reporting official inflation

statistics during the worst months of the country's hyperinflation, the

report uses standard economic theory (comparisons of purchasing power

parity) to determine Zimbabwe's worst rates of inflation.

With prices almost doubling every 24 hours, just days after issuing a $100 million bill, the Reserve Bank issued a $200 million bill and capped bank withdrawals at $500,000, which at the time was equal to about $0.25 US. When the $100 million bill was introduced, prices soared, and reports from the country described that the price for a loaf of bread rose from $2 million to $35 million overnight. At one point, the government even declared inflation to be "illegal" and arrested the executives of companies for raising prices on their products.

The situation became so dire that shops in the country simply began refusing the currency and the US dollar, as well as the South African rand became the de facto medium of exchange. Inflation finally came to the end with direct intervention by the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe that re-priced the currency, pegging it to the US dollar. The government also issued regulations that shut down the country's stock exchange.

With prices almost doubling every 24 hours, just days after issuing a $100 million bill, the Reserve Bank issued a $200 million bill and capped bank withdrawals at $500,000, which at the time was equal to about $0.25 US. When the $100 million bill was introduced, prices soared, and reports from the country described that the price for a loaf of bread rose from $2 million to $35 million overnight. At one point, the government even declared inflation to be "illegal" and arrested the executives of companies for raising prices on their products.

The situation became so dire that shops in the country simply began refusing the currency and the US dollar, as well as the South African rand became the de facto medium of exchange. Inflation finally came to the end with direct intervention by the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe that re-priced the currency, pegging it to the US dollar. The government also issued regulations that shut down the country's stock exchange.

Causes of Zimbabwe's Inflation

When Zimbabwe gained independence in 1980, the

country adopted a new currency that was originally valued at

approximately $1.25 US. The country's eventual out-of-control inflation

was caused almost entirely by governmental mismanagement.

The path towards hyperinflation began in the early 1990s when President Robert Mugabe initiated a series of land redistribution programs that took land from the country's ethnically European farmers and gave the land to ethnic Zimbabweans. The sudden removal of an entrenched and experienced farmer class severely damaged the country's capacity for food production, dropping supply far below demand and raising prices as a result.

Early in the 21st century, Zimbabwe entered hyperinflation and by 2006 the country printed 21 trillion ZWD to pay off loans from the IMF. Later that year, the country again had to print money, in excess of 60 trillion, in order to pay salaries of soldiers, policemen and other civil servants. In 2007, there were extreme shortages of basic food, fuel, and medical supplies as IMF estimates for monthly inflation increased over 115,000 percent by the end of the year and the Zimbabwe government instituted a 6-month freeze on wages that September.

By April 2008, the $50 million note was equivalent to $1.20 US, while the central bank estimated that country's economy contracted over 6 percent from a year prior. The LA Times reported in July 2008 that the government ran out of paper on which to print money as European suppliers of the paper stopped supplying the country due to humanitarian concerns.

In sum, the widespread contraction of the economy, severe shortages of basic goods and serious lapses in government policy all contributed in Zimbabwe's spiral into hyperinflation.

The path towards hyperinflation began in the early 1990s when President Robert Mugabe initiated a series of land redistribution programs that took land from the country's ethnically European farmers and gave the land to ethnic Zimbabweans. The sudden removal of an entrenched and experienced farmer class severely damaged the country's capacity for food production, dropping supply far below demand and raising prices as a result.

Early in the 21st century, Zimbabwe entered hyperinflation and by 2006 the country printed 21 trillion ZWD to pay off loans from the IMF. Later that year, the country again had to print money, in excess of 60 trillion, in order to pay salaries of soldiers, policemen and other civil servants. In 2007, there were extreme shortages of basic food, fuel, and medical supplies as IMF estimates for monthly inflation increased over 115,000 percent by the end of the year and the Zimbabwe government instituted a 6-month freeze on wages that September.

By April 2008, the $50 million note was equivalent to $1.20 US, while the central bank estimated that country's economy contracted over 6 percent from a year prior. The LA Times reported in July 2008 that the government ran out of paper on which to print money as European suppliers of the paper stopped supplying the country due to humanitarian concerns.

In sum, the widespread contraction of the economy, severe shortages of basic goods and serious lapses in government policy all contributed in Zimbabwe's spiral into hyperinflation.

#3: Yugoslavia, January 1994

Highest monthly inflation: 313,000,000%

Prices doubled every: 1.4 days

Another

extreme case of hyperinflation with the Yugoslavian dinar between

1993-1995. The steepest rate of inflation during this period was in

January 1994, when prices rose 313 million percent over the month, which

is equivalent to 64.6 percent per day, with prices doubling

approximately every 34 hours. During the entire period of inflation, it

is estimated that prices increased by 5 quadrillion percent.

Eventually, many Yugoslavian businesses refused the dinar and the German Deutsche Mark (DM) became the unofficial currency of the country, even after the government revalued the dinar by converting 1 million dinars to 1 "new" dinar. According to an analysis by Prof. Thayer Watkins of San Jose State University, on November 12, 1993, 1 DM = 1 million new dinars. By December 15th 1 DM was equivalent to 3.7 billion dinars and by the end of the month the exchange rate reached a level of 1 DM = 3 trillion dinars.

After a second revaluation, 1 "new new" dinar was equivalent to 1 billion "old new" dinars and after this 1 DM = 6,000 dinars. By January 17th, the exchange rate shot up to 1 DM = 30 million dinars and on January 24th the government introduced the "super" dinar, equal to 10 million "new new" dinars, marking the 5th revaluation of the currency.

Throughout the period, the government had an extremely difficult time maintaining the social structure of the country after ineffective price controls exacerbated the problems, government agencies were virtually unable to operate and residents avoided paying bills on time since they would be devalued so rapidly.

Eventually, many Yugoslavian businesses refused the dinar and the German Deutsche Mark (DM) became the unofficial currency of the country, even after the government revalued the dinar by converting 1 million dinars to 1 "new" dinar. According to an analysis by Prof. Thayer Watkins of San Jose State University, on November 12, 1993, 1 DM = 1 million new dinars. By December 15th 1 DM was equivalent to 3.7 billion dinars and by the end of the month the exchange rate reached a level of 1 DM = 3 trillion dinars.

After a second revaluation, 1 "new new" dinar was equivalent to 1 billion "old new" dinars and after this 1 DM = 6,000 dinars. By January 17th, the exchange rate shot up to 1 DM = 30 million dinars and on January 24th the government introduced the "super" dinar, equal to 10 million "new new" dinars, marking the 5th revaluation of the currency.

Throughout the period, the government had an extremely difficult time maintaining the social structure of the country after ineffective price controls exacerbated the problems, government agencies were virtually unable to operate and residents avoided paying bills on time since they would be devalued so rapidly.

Causes of Yugoslavia's Inflation

The causes of Yugoslavia's hyperinflation stem

from conflict in the region, local economic crises and governmental

mismanagement.

Following a recession sparked by excessive overseas borrowing and a block on exports in the 1970s, the country and region was mired in conflict and political struggle throughout the '80s and early '90s. After accepting an IMF loan following a deep recession, in 1989 and 1990 over 1,100 firms went bankrupt and in a workforce of about 2.7 million, more than 600,000 workers were laid off. In addition, some companies seeking to avoid bankruptcy stopped paying workers for the first few months of the year, affecting an estimated 500,000 individuals.

The Yugoslav Wars, the breakup of the state and general destabilization of the region were major contributing factors to hyperinflation. Government mismanagement, including ill-conceived economic policies like unrestrained printing of money, generation of large deficits and price setting exacerbated the situation greatly.

Price controls were specifically troublesome. Enacted by the government, they presented disincentives for farmers who could no longer profit from selling their crops and as a result, stores closed to save their inventory instead of selling at artificially low, government-set prices. The government also began buying items from overseas instead of removing price controls and alleviating the country's supply, distribution and monetary problems. As supply shrank dramatically, prices exploded as goods became increasingly scarce.

In the case of Yugoslavia, the drastic imbalance of supply and demand, combined with an faltering government and unchecked printing of currency were the root causes of the country's massive inflation.

Following a recession sparked by excessive overseas borrowing and a block on exports in the 1970s, the country and region was mired in conflict and political struggle throughout the '80s and early '90s. After accepting an IMF loan following a deep recession, in 1989 and 1990 over 1,100 firms went bankrupt and in a workforce of about 2.7 million, more than 600,000 workers were laid off. In addition, some companies seeking to avoid bankruptcy stopped paying workers for the first few months of the year, affecting an estimated 500,000 individuals.

The Yugoslav Wars, the breakup of the state and general destabilization of the region were major contributing factors to hyperinflation. Government mismanagement, including ill-conceived economic policies like unrestrained printing of money, generation of large deficits and price setting exacerbated the situation greatly.

Price controls were specifically troublesome. Enacted by the government, they presented disincentives for farmers who could no longer profit from selling their crops and as a result, stores closed to save their inventory instead of selling at artificially low, government-set prices. The government also began buying items from overseas instead of removing price controls and alleviating the country's supply, distribution and monetary problems. As supply shrank dramatically, prices exploded as goods became increasingly scarce.

In the case of Yugoslavia, the drastic imbalance of supply and demand, combined with an faltering government and unchecked printing of currency were the root causes of the country's massive inflation.

#4: Germany, October 1923

Highest monthly inflation: 29,500%

Prices doubled every: 3.7 days

Hyperinflation was one of the major problems plaguing Germany's Weimar republic during its last years of existence. Reaching a monthly inflation rate of approximately 29,500 percent in October 1923, and with an equivalent daily rate of 20.9 percent it took approximately 3.7 days for prices to double.

The German papiermark, which was introduced in 1914 when the country's gold standard was eliminated, began with an exchange rate of 4.2 per US dollar at the outbreak of WWI up to 1 million per US dollar in August 1923. By November, that number had skyrocketed to about 238 million papiermark to 1 US dollar, and a psychological disorder called "Zero Stroke" was coined, after people were forced to transact in the hundreds of billions for every day items and were dizzied by the amount of zeros involved.

The rapid inflation caused the government to issue a redenomination, thus replacing the papiermark with the rentenmark, exchanging at a rate of 4.2 per US dollar and cutting 12 zeros off of the papiermark's face value. Although the retenmark effectively stabilized the currency and the Weimar republic continued to exist until 1933, hyperinflation and its resulting economic pressures contributed to the rise of the Nazi party and Adolf Hitler, who focused explicitly on Germany's economic situation in Mein Kampf.

Causes of Germany's Inflation

Although many believe that hyperinflation of the Weimar Republic resulted directly from the government printing money to pay war reparations, the roots of country's painful inflation situation developed years earlier.

In 1914, Germany abandoned backing their currency with gold and began financing their war operations through borrowing instead of taxation. By 1919, prices had already doubled and Germany lost the war, but the period between 1919 and 1921 was relatively stable for the currency, compared to the following years.

The war reparations demanded by the Treaty of Versailles required expenses to be paid for with a gold or foreign currency equivalent, instead of German papiermarks, so the government could not simply inflate their way out of their debts. However, to purchase foreign currencies, the government used government debt-backed papeirmarks and accelerated the devaluation of their currency.

When the Germans became delinquent in their payments, French and Belgian troops occupied the industrialized Ruhr Valley in January 1923 to demand reparation payments in hard assets, causing strikes and passive resistance among workers that worsened the situation. With European governments conflicted on how best to deal with the situation, Germany's economy quickly imploded and for over a year and a half the country was in a state of hyperinflation.

#5: Greece, October 1944

Highest monthly inflation: 13,800%

Prices doubled every 4.3 days

In the fifth worst inflation situation of all time, Greece in 1944 saw prices double every 4.3 days. Hyperinflation in Greece technically began in October 1943, during the German occupation of the country in WWII. However, the most rapid inflation occurred when the Greek government in exile regained control of Athens in October 1944; prices rose by 13,800 percent that month and another 1,600 percent in November, according to a study by Gail Makinen.

In 1938, the Greeks held a drachma note for an average of 40 days before spending it, but by November 10th 1944, the average holding time shrunk to 4 hours. In 1942, the highest denomination of currency was 50,000 drachma, but by 1944 the highest denomination was a 100 trillion drachmai note. On Nov 11th, the government issued a redenomination of the currency, which converted old drachmai to new at a rate of 50 billion to one, although the populace continued using British Military Pounds as the de facto currency until mid-1945.

The stabilization efforts were relatively successful, with prices rising only 140 percent from January through May, and even seeing 36.8 percent deflation in June 1945 when prominent economist Kyriakos Varvaressos was brought in as economic czar. However, his plan of increasing foreign assistance, reviving domestic production and imposing controls on wages and prices through a redistribution of wealth worsened the country's budget deficit and Varvaressos resigned on September 1.

After the civil war of Jan-Dec. 1945/46, the British offered a plan to stabilize the country, which included increasing revenues through the sale of aid goods, an adjustment of specific tax rates, improved tax collection methods and the creation of the Currency Committee (composed of three Greek Cabinet Ministers, one Briton and one American) for fiscal responsibility. By the beginning of 1947, prices had stabilized, public confidence was restored and national income rose, bringing Greece out of the vortex of hyperinflation.

Causes

of Greece's Inflation

The main cause of Greece's

hyperinflation was World War II, which loaded the country with debt, dissolved

its trade and resulted in four years of Axis occupation.

At the outset of World War II, Greece saw a budget surplus for fiscal 1939 of 271 million drachma, but this slipped to a deficit of 790 million drachma in 1940, due mostly to trade, reduced industrial production as a result of scarce raw materials and unexpected military expenditures. The country's deficits would continue to be funded by monetary advances from the Bank of Greece, which had doubled the money supply in two years.

With tax revenues down and military expenditures up nearly 10-fold, Greece's finances were in a downward spiral. The country was occupied by Axis forces by May 1941, and Greece's military costs were replaced by expenditures from the support of 400,000 troops, which varied between one-third and three-fifths of the country's outlays during the occupation, which were all funded by the printing of money by the Bank of Greece. The Greek puppet government - established by the occupying forces - did not tax to cover its costs and revenues represented less than 6 percent of expenditures during the final year of occupation. This was combined with national income dropping from 67.4 billion drachma in 1939 to 20 billion in 1942, a level that was maintained until 1944.

Hyperinflation began in 1943, when expectations of future inflation caused Greeks to refuse to accept the currency and the government began paying in gold franc coins, which further encouraged the public to hold wealth in non-currency forms and decreased confidence in the drachma, reducing the elasticity of and the demand for domestic currency. When the government in exile returned to Athens, they had a limited ability to collect taxes outside of the capital and ran into substantial unemployment and refugee costs. By the time the new government's stabilization effort went into effect, revenues comprised 0.4 percent of expenditures, with the Bank of Greece covering the rest.

The stabilization effort occurred while the war was still going on, a civil war broke out and there was little hope of restoring Greece's export trade (traditionally with members of the Axis) or the import of raw materials, dipping the country back into high inflation once more before the currency finally stabilized.

http://tinyurl.com/ammvkl9

No comments:

Post a Comment