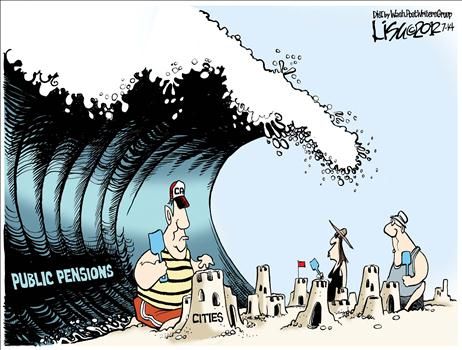

A glimpse into the public-union mind-set

Rhode Island’s Democratic state treasurer, Gina Raimondo, is fond of saying that pension reform is about math, not politics. Other blue-state politicians, ranging from New York governor Andrew Cuomo to Chicago mayor Rahm Emanuel, have moved toward fixing unsustainable pensions. But California’s top statewide political leaders have mostly shrugged

at the problems caused by excessive pay and benefit packages granted to

public-sector workers. The state faces an unfunded pension liability of

at least $300 billion, and major cities—notably Stockton and San Bernardino—are taking the municipal-bankruptcy route; even Los Angeles

is mulling the option. Until recently, even the most modest reforms to

California’s public-employee compensation have gone nowhere—and though

Democrats are now suddenly talking about tackling some kind of pension

reform within the next four weeks, history suggests that it’s wise to be

skeptical.

What is it about California’s Democratic leaders that makes them

ignore fiscal reality and put politics above mathematics? Conventional

wisdom holds that unions elect these politicians and that the

politicians do the unions’ bidding. But in reality, the unions are

the legislature. Most of the Democratic leadership in the state

assembly and senate comes directly out of the union movement and

identifies with the public sector. For these union Democrats, government

is primarily a means to improve the financial condition of those who

work for the government.

The best articulation of this vision can be found in a speech that

state treasurer Bill Lockyer gave last October. “As a California public

official, I also believe in the principle that our nation and our state

have an absolute obligation, to every American and every Californian, to

ensure that when the time comes for them to put down the tools and

enjoy a well-deserved retirement, those workers can live the rest of

their lives with dignity and good health, and not in poverty,” Lockyer

said. “And in my view, nothing is more important in providing for

retirement security than preserving the defined benefit pension for

those who have it, and restoring and reinvigorating the defined benefit

leg of the three-legged retirement stool for those across the country

who have lost it in the space of a few short years.” Lockyer conceded

that “pension liabilities are a problem,” but only because “they

are driving unacceptably high contribution rates for employers and

workers, too.” In other words, public pensions are a concern not because

of the costs to taxpayers but because of the burden they place on

government agencies and government employees. To ease that burden, union

Democrats want—what else?—new taxes.

Sacramento Bee reporter Jon Ortiz, who covers state workers

and unions, wrote that Lockyer’s speech “echoed the new argument that

public employee unions are making in defense of retirement benefits.”

And this year, the public got to see an incongruous legislative

manifestation of Lockyer’s argument. Los Angeles Democrat Kevin de

León’s Assembly Bill 1234 would have the state, in effect, create a

miniature Social Security system designed to bolster private

retirement accounts—albeit at a much lower rate of return and with much

lower benefits than those enjoyed by retired public employees. De León’s

bill passed the state senate and awaits a hearing before the assembly’s

appropriations committee—incredible as it may seem, given the

legislature’s refusal to give public-pension reform any serious thought.

The reason for the de León bill is union Democrats’ belief that the

pension problem is merely, as Lockyer puts it, “a very serious and

virulent strain of pension envy.” Instead of fixing the unsustainable

public-pension system—which they regard as a success that has helped a

portion of the public receive the kind of comfortable retirement that

everyone should have—the union Democrats want to throw a few bones to

private-sector workers afflicted with this “pension envy.”

Lockyer’s intransigence illustrates why San Jose mayor Chuck Reed

says that getting any reform out of Sacramento is hopeless. Reed, of

course, spearheaded a successful pension-reform ballot initiative that

unions are now challenging

in court. If pension reform succeeds in the Golden State, it will

happen at the ballot box—in spite of the best efforts of union

Democrats, who continue to defend the indefensible.

No comments:

Post a Comment