General

Martin Dempsey, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, has

concluded that generals do not live up to the standards they demand of

others. According to the New York Times,

“Under General Dempsey’s plan, teams of inspectors will observe and

review the procedures . . . in effect for all generals. He said he would

be subject to the same rules.”

Those new rules would seem to

require an assessment of Dempsey’s own performance last September, when

he decided not to respond with force to the terrorist attack in Benghazi

for ten hours, although our ambassador to Libya was declared missing

during the first hour of the assault and two former SEALs died in the

tenth hour. Why did Dempsey choose to do nothing?

The military has

conducted hundreds of assessments for battles throughout Iraq and

Afghanistan. At the platoon level, an “After Action” critique is

required whenever there are American fatalities. But at the highest

level, there has been no military After Action assessment about

Benghazi.

The fight at the U.S. consulate waxed and waned for ten

hours. Yet during that time, the Marine Force Recon unit on Sigonella

Air Base, 500 miles away, was never deployed and not one F-16 or F-18

was dispatched. Granted, Force Recon and fighter aircraft weren’t on

alert and did not appear on the Pentagon’s official list of “hostage

rescue forces.” But they were one phone call away, and no general asked

for them. Ten hours provided adequate time for a range of ad hoc

responses. Commanders are expected to adapt in battle.

Pentagon

spokesman George Little said, “We have repeatedly stated that . . . our

forces were unable to reach it in time to intervene to stop the

attacks.” That is true only if the Pentagon is incapable of improvising.

If you see people in a burning house, you do your best to help

immediately; you don’t wait for the fire department to respond in a

normal manner. If called upon, the Marines on Sigonella would have

gathered whoever was on hand and piled into one of a dozen military

planes parked at the base. The Benghazi airport 90 minutes away was

secure; CIA operatives were standing on the runway, because they had

improvised by hiring a plane and flying in from the embassy in Tripoli,

400 miles away. A fighter jet could have refueled at that airport, with

the CIA providing cover. Instead, the military ordered four Special

Operations soldiers at the Tripoli embassy not to fly to Benghazi and

join the CIA team.

The military did nothing, except send a drone

to watch the action. Defense Secretary Panetta later offered the excuse,

“You can’t willy-nilly send F-16s there and blow the hell out of place.

. . . You have to have good intelligence.” As a civilian, Mr. Panetta

probably didn’t know that 99 percent of air sorties over Afghanistan

never drop a single bomb. General Dempsey, however, knew it was standard

procedure to roar menacingly over the heads of mobs, while not “blowing

the hell out of them.” A show of air power does have a deterrent effect

and is routinely employed.

A mortar shell killed two Americans

during the tenth hour of the fight. A mortar tube can be detected from

the air. The decision whether to then bomb should have resided with a

pilot on-station — not back in Washington. As for the alleged lack of

“good intelligence,” three U.S. operations centers were watching

real-time video and talking by cell phone with those under attack.

Surely that comprises “good intelligence.”

Dempsey’s predecessor

as chairman of the joint chiefs, Admiral Mike Mullen, co-chaired an

assessment for the State Department. Mullen conveniently inserted a

one-sentence judgment about the Pentagon, asserting the military could

not do anything. Yet most generals would relieve a company commander who

possessed intelligence for ten hours and did nothing. This appearance

of a rigid standard for the grunt and a lax standard for generals is

precisely what General Dempsey wants to correct.

If General

Dempsey is serious about one set of rules for all generals, then he will

demand an assessment of his own performance. This is not a call for a

resignation. Dempsey is admired for his openness, flexibility, and

commonsense. In 2004, he redeployed on the fly his entire division in

order to protect Baghdad. At least three four-star generals and three

separate staffs (the operations centers in the Pentagon, Special Ops in

Tampa, and Africom in Germany) watched the ten-hour action. The issue is

not one of personalities. At one time or another, most of us choke in

combat or during a crisis; look at the number of CEOs caught flat-footed

during the 2008 financial crisis.

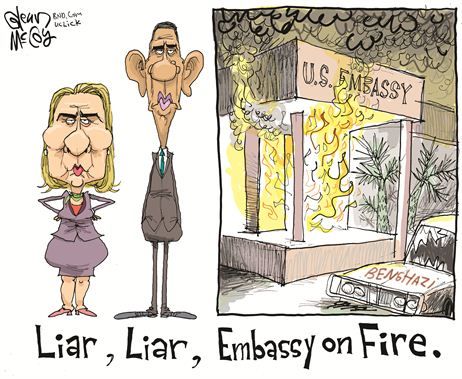

To be clear: the non-response

by the military is a matter of procedures too rigid at the top. Far more

serious and of a different nature was the claim that a video had

provoked a spontaneous mob and that Benghazi was not a terrorist attack.

That was the deliberate manipulation or fictional creation of

intelligence. It raises the matter of deception. Who provided that

rationale to U.N. ambassador Susan Rice? That is a grave issue that has

nothing to do with the military.

The integrity of the Pentagon is

not in question. The purpose of an After Action is to perform better the

next time. Is the public seriously to believe that in ten hours Dempsey

and the $600 billion dollar Defense Department could not dispatch one

ad hoc rescue team, as our embassy in Tripoli did, or order one fighter

jet to scramble?

Have our military’s best and brightest lost the

capacity to improvise? Clearly, that merits an assessment. Will General

Dempsey ask for a review of his own procedures?

Do as I say, or as I do?

The chairman of the joint chiefs is the only general who can answer

that.

— Bing West, a former assistant

secretary and combat Marine, has written seven books about combat in

Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan.

By David French

I hope military and civilian policy makers carefully read Bing West’s post

responding to various excuses advanced for failing to aid embattled

Americans in Benghazi on September 11, 2012. I could never improve on a

Bing West military analysis, but let me also add that September 11,

2012, was a profound moral failure. The degree of courage displayed that

night was apparently inversely proportional to the

decision-maker’s distance from Libya. The Americans on the scene fought

valiantly, outgunned (by a rag-tag band of terrorists, no less; thanks

to inexcusably negligent decisions to drawdown before the attack), with

men giving their lives in a successful effort to prevent even greater

carnage. Other Americans in Libya made desperate efforts to reach the

embattled compound in time. The Americans in Washington? In Italy?

Elsewhere in our vast and expensive military/civilian national-security

apparatus? They failed.

As I noted in Patheos last November, the peace and prosperity of the great mass of Americans depends to a large degre on the willingness of a certain, small number of their fellow citizens to forgo that peace and prosperity, to stand “on the wall” as warriors or — in the case of Ambassador Stevens and those lost last September — as diplomats in harm’s way. We need men and women who are ready to lay down their lives to defeat our enemies when they must and risk their lives to extend the hand of friendship when they should.

We can never adequately repay these individuals, but one thing we must do: promise that we’ll never leave them behind. This is the heart of the Soldier’s Creed: “I will never leave a fallen comrade.” In the military, it is difficult to overstate the sense of betrayal – of anguish – if any soldier feels this sacred pledge has been violated. Absent the most compelling of circumstances, if you violate that pledge, you commit a grave injustice. If you later lie, seek to cover up your failure, or fail to “man up” and explain why you didn’t send help, then you have no shame.

If the most current reports can be believed, after depriving our men and women on the ground of the security they begged for, our leaders didn’t just stand by and watch as a tiny band of courageous but out-gunned Americans gave their last full measure of devotion to try to save an ambassador, save their fellow diplomats, and save themselves against an overwhelming terrorist force, those same leaders told potential rescuers to “stand down.” This isn’t just a tactical failure, or a failure of process. It’s a failure of character, and if there is any honor left in Washington, those responsible should resign.

As I noted in Patheos last November, the peace and prosperity of the great mass of Americans depends to a large degre on the willingness of a certain, small number of their fellow citizens to forgo that peace and prosperity, to stand “on the wall” as warriors or — in the case of Ambassador Stevens and those lost last September — as diplomats in harm’s way. We need men and women who are ready to lay down their lives to defeat our enemies when they must and risk their lives to extend the hand of friendship when they should.

We can never adequately repay these individuals, but one thing we must do: promise that we’ll never leave them behind. This is the heart of the Soldier’s Creed: “I will never leave a fallen comrade.” In the military, it is difficult to overstate the sense of betrayal – of anguish – if any soldier feels this sacred pledge has been violated. Absent the most compelling of circumstances, if you violate that pledge, you commit a grave injustice. If you later lie, seek to cover up your failure, or fail to “man up” and explain why you didn’t send help, then you have no shame.

If the most current reports can be believed, after depriving our men and women on the ground of the security they begged for, our leaders didn’t just stand by and watch as a tiny band of courageous but out-gunned Americans gave their last full measure of devotion to try to save an ambassador, save their fellow diplomats, and save themselves against an overwhelming terrorist force, those same leaders told potential rescuers to “stand down.” This isn’t just a tactical failure, or a failure of process. It’s a failure of character, and if there is any honor left in Washington, those responsible should resign.

No comments:

Post a Comment