One of the Left's favourite 'conservatives,' David Frum asked a serious question yesterday, to wit: Remember when Democrats opposed the imperial presidency?

But what’s happened with Executive power is weirder than a mere rotation in the respective chances of Rs and Ds in presidential elections. There are strong substantive reasons why you’d expect modern conservatives to favor the Executive and modern liberals to mistrust it. The Executive commands the war-making power of the American state. Intelligence agencies answer to the Executive, and the Executive is in turn powerfully shaped by its relationship with those agencies. The Executive is elected in broad national elections in which discrete and insular minorities carry less weight.

It is the Executive that is held responsible when budgets don’t balance, for the stability of the currency, for the performance of the American economy. The presidency makes cautious even the most ambitious reformers.

It’s not a coincidence that—with only very partial exception of Barack Obama—none of the presidents elected since 1945 has enjoyed during his time in office anything like the popularity among political liberals that Richard Nixon, Ronald Reagan, and George W. Bush enjoyed among conservatives during theirs.

So it’s all in all a real surprise that it should be Senate Democrats who struck this blow for the Hamiltonian conception of the presidency—and against their own personal power.

Read the Article

'While we are followers of Jefferson, there is one principle of Jefferson's which no longer can obtain in the practical politics of America. You know that it was Jefferson who said that the best government is that which does as little governing as possible...BUT THAT TIME HAS PASSED. AMERICA IS NOT NOW AND CANNOT IN THE FUTURE BE A PLACE FOR UNRESTRICTED INDIVIDUAL FREEDOM AND ENTERPRISE.'

- Woodrow Wilson

The Left has always loved the imperial presidency…as long as their man was in the Oval Office. You can go back and read the writings of a certain Professor of political science and history at Bryn Mawr and then Wesleyan to begin to see the Progressives reject the founding documents and principles of this country. This Progressive Ph.D had no tolerance and patience for the aggravations and messiness that are hallmarks of Republican forms of democracy. In fact, the man, who would become what I call the First Fascist President of the United States, held his fellow citizens in contempt considering uneducated, incompetent children, who were incapable of making the best decisions for themselves, their children, their finances, and their communities.

The lack of restrictions on the vox populi and their rights to participate in their own government and to make demands upon the wise and worldly men, who are rightly entitled to run the country would lead to national ruin, if not populicide. These unwashed hoi polloi would, ultimately, bring about the country's utter destruction and demise.

Even before he became President of Princeton and Governor of New

Jersey, he had a firm idea of how the Federal government should work

with the Executive being supreme. The idea of three co-equal branches of government and the Separation of Powers

were just antiquated notions. After all, the argument went, who would be better capable of efficiently running a reform government? Legions of expert bureaucrats educated in the country's finest universities where they were matriculated in the 'ideas and philosophies of the future' such as those espoused by Hegel, Rousseau, Kant, Marx, Nietzsche, Galton, Darwin, and Bismarck, among others, could

run the government more competently enlightened than politicians elected by rubes and hayseeds with old-fashioned notions of freedom and individuality.

This largely dry essay on public administration, published by Woodrow Wilson during the time he taught at Bryn Mawr College, makes a revolutionary argument for a professional centralized administration in the United States. Introducing a novel distinction between politics and administration, Wilson demands a bureaucracy that would govern independently from the elected branches of government. In doing so, he walls off the founding principles of consent of the governed and the separation of powers from the emerging new science of administration.

The essay, published in the Political Science Quarterly in July 1887, advocates a trained bureaucracy that has the expertise and the will to oppose popular opinion when they deem it necessary. In contrast to the founding principle of equality—meaning that claims to superior wisdom cannot justify rule and that legitimate government is based on the consent of the governed—Wilson argues that expertise is a title to rule.

Wilson’s faith in the rule of experts is coupled with a profound distrust of republican self-government: “The bulk of mankind is rigidly unphilosophical, and nowadays the bulk of mankind votes.” Democracy has empowered thousands upon thousands of the “selfish, ignorant, timid, stubborn, or foolish,” who come from a mix of different nationalities. All hope is not lost, however, since there are “hundreds who are wise.” Wilson’s charge is to recruit for the bureaucracy from these wise hundreds, produce more of them, and “open for the public a bureau of skilled, economical administration.”

Wilson realizes that such a view of administration is a hard sell to Americans, who prefer democracy to “officialism.” Thus, reformers must eschew “theoretical perfection” and defer to “American habit” and know-how. In turn, Americans, Wilson admonishes, need to rid themselves of “the error of trying to do too much by vote. Self-government does not consist in having a hand in everything, any more than housekeeping consists necessarily in cooking dinner with one’s own hands” (emphasis added). Wilson would replace amateur cooks with professionals. Eventually the entire household will be run by professionals. The practice of self-government through elected officials will be lost as “considerate, paternal government” fulfills all needs. The master of the house will become utterly dependent on his professional retinue.

The trained servants will tutor the people by improving public opinion and thereby even ultimately ruling them. The bureaucracy would educate the electorate. Wilson modestly claims that his ideal is “a civil service cultured and self-sufficient enough to act with sense and vigor, and yet so intimately connected with the popular thought, by means of elections and constant public counsel, as to find arbitrariness of class spirit quite out of the question.” Yet once the bureaucracy, aided by the universities, asserts itself against the elected branches and the people in the name of its expertise, the people could no longer defend themselves.

- Woodrow Wilson on Administration, Heritage. The entire text of the essay entitled The Study of Administration by Woodrow Wilson and published in the Political Science Quarterly, July 1887, is available here.

He was joined in this movement by fellow Progressives like close-friend and adviser, Colonel Edward House and 'The Four Horsemen of the Progressive Apocalypse': Richard

Ely, John Dewey, Herbert Croly, Oliver Wendel Holmes, among others.

He, of course, was Thomas Woodrow Wilson.

He wasn’t the only President to take such a view of the office. FDR

demanded – and received – a Congressional order allowing him to act as

Commander-in-Chief in fighting the depression. He could do what he

wanted with the assistance of his ‘(Red) Brain Trust’ like Rexford

Tugwell, Harry Dexter White, and Henry Wallace, to name a few.

I hope you enjoy the following look at the Progressive worldview and origins from the 31 December 2009 issue of National Review.

The Progressives

Jonah Goldberg, Tiffany Jones Miller, Bradley C. S. Watson, and Fred Siegel profile four intellectual architects of Obaman liberalism: Richard Ely, John Dewey, Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., and Herbert Croly.

Richard Ely’s Golden Calf

By Jonah Goldberg

In a lecture to Harvard students in 1886, Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr.

spoke of the sort of thinker of whom it can be said that, “a hundred

years after he is dead and forgotten, men who never heard of him will be

moving to the measure of his thought.”

Perhaps more than any other leading progressive intellectual, Richard

Ely is dead and forgotten, save among a few economists and a few

historians. The American Economic Association, which Ely founded, still

has a prestigious Richard Ely memorial lecture, and such

neo-progressives as the late Richard Rorty

tried valiantly to restore Ely’s stature. But for the most part, Ely is

the answer to a very obscure trivia question. And yet today’s liberals

continue to move to the measure of his thought.

With only a modicum

of literary license, it’s fair to say that the house of contemporary

liberalism sits on a foundation laid down by Ely. He

wrote dozens of books, on monopoly, taxation, land use, and urban

reform, and several standard texts on general economics. A leader of the new generation of German-trained or -inspired Ph.D.s, Ely began teaching at the brand-new Johns Hopkins University

— conceived as a German-style institution — in 1881. Just over a decade

later, the progressive writer Lyman Powell wrote that Ely’s writings

“exercised a wider and more positive influence on American legislation

than the works of any other economist of the present generation.” Not

long after that, he was known as the “dean of American economics.”

As a professor at Hopkins and, later, the University of Wisconsin, Ely served as a mentor to or major influence on many of the most important progressive thinkers and activists. In 1939, a reviewer of Ely’s autobiography, Ground under Our Feet,

observed that “it is common knowledge, among those who know the field,

that Dr. Ely has a greater ‘gallery’ [of disciples] than any other

economics professor in the country.” His disciples and allies became the intellectual shock troops of progressivism in journalism and academia.

His student John Finley was, variously, president of the City College

of New York, New York state commissioner of education, and

editorial-page editor of the New York Times. Msgr. John A.

Ryan, whose writings on industrial democracy were integral to the New

Deal, was one of Ely’s greatest champions (Ely found a publisher for

Ryan’s 1906 book A Living Wage and wrote the introduction to it).

The most famous

members of Ely’s gallery, however, were politicians: Woodrow Wilson,

Ely’s student at Hopkins; Wisconsin governor Robert La Follette Sr.; and

Theodore Roosevelt. Ely’s influence on La Follette was

extensive, as Ely was the leading academic behind the “Wisconsin Idea” —

using academic experts to guide government policy — and La Follette,

who often called Ely his “teacher,” was its foremost political champion.

His influence on Teddy Roosevelt was more diffuse. While they were

longtime friendly acquaintances, Ely’s impact on TR came mostly through

his writings and through Albert Shaw, a student and devotee of his who

became a close adviser to Roosevelt. TR famously said of Ely, “He first introduced me to radicalism in economics and then made me sane in my radicalism.”

That “radicalism” was mainstream progressive economics, or simply

“reform.” Some of the reforms were perfectly defensible. Clean food and

drinking water, the improvement of labor conditions, the abolition of

child labor are all desirable ends, even if we can debate the means of

attaining them. And while much of the welfare state that we know today

was constructed by the “new economists” Ely led, his more significant

contribution was not, strictly speaking, economic.

Many contemporary

progressives assert that liberalism is an authentic American tradition,

with roots in American soil. In part because the word “liberal” came to

have a foreign or un-American patina to it, many prominent liberals have

adopted “progressive” instead. During a 2007 primary

debate, Hillary Clinton rejected the “liberal” label. “I prefer the word

‘progressive,’ which has a real American meaning, going back to the

progressive era at the beginning of the 20th century.”

The irony here is

that the supposedly more authentically American tradition of reform also

has a heavily European lineage. Indeed, American progressives saw

themselves as the U.S. franchisees of an international effort.

“We were parts, one of another, in the United States and Europe,”

proclaimed William Allen White. “Something was welding us into one

social and economic whole with local political variations. It was Stubbs

in Kansas, Jaurès in Paris, the Social Democrats [that is, the

Socialists] in Germany, the Socialists in Belgium, and I should say the

whole people in Holland, fighting a common cause.” When Jane Addams

seconded Teddy Roosevelt’s nomination at the Progressive-party

convention in 1912, she declared, “The new party has become the American

exponent of a world-wide movement toward juster social conditions, a

movement which the United States, lagging behind other great nations,

has been unaccountably slow to embody in political action.”

If America was lagging behind, Germany was leading the pack.

Bismarck’s “top-down socialism” was, in the words of liberal historian

Eric Goldman, “a catalytic of American progressive thought.” A young

Woodrow Wilson wrote that Bismarck’s Prussia was the most “admirable

system . . . the most studied and most nearly perfected” in the world.

When the American Economic Association was formed, five of the first six

officers had studied in Germany. At least 20 of its first 26 presidents

had as well. In 1906, a professor at Yale polled the top 116 economists

and social scientists in America; more than half had studied in Germany

for at least a year.

Much of the philosophical rationale for Bismarck’s top-down socialism

came from the “historical school” of German economists, of which Ely’s

mentor at the University of Heidelberg, Karl Knies, was a leader. Imbibing heavily from Hegel and Darwin,

the historicist economists believed that all economic facts are

relative and evolutionary, contingent upon their time and place.

Historicists rejected laissez-faire economics on the grounds that there

are no immutable or universal laws of economics. “The

most fundamental things in our minds,” Ely said of himself and his new

generation of intellectuals, “were on the one hand the idea of

evolution, and on the other hand, the idea of relativity.”

“The nation in its economic life is an organism,” he wrote, “in which

individuals, families, and groups . . . form parts.” Hence competition

and self-interest are generally bad things, working against the tide of

progress. After all, organs in the human body do not compete against one

another, so why should organs of the body politic? History, like

evolution itself, was moving toward greater social cooperation. And it

fell to experts to decide how to advance that process.

Not only did this vision provide a perfect rationale for empowering social planners, it necessarily consigned the rights and liberty of the individual to being an afterthought — hence Ely’s advocacy of what he called “coercive philanthropy.” If experts can glean which way social betterment lies, who is the individual to object? The job of the economist is not to consider discrete questions about how to, say, maximize productivity or measure discretionary income. It is to fix society in all its relations, right down to each individual. The goal of the economist, Ely believed, was to hasten “the most perfect development of all human faculties in each individual.” Whether the individual wanted that development was irrelevant.

“A new world was coming into existence, and if this world was to be a better world we knew that we must have a new economics to go along with it.”

Not only did this vision provide a perfect rationale for empowering social planners, it necessarily consigned the rights and liberty of the individual to being an afterthought — hence Ely’s advocacy of what he called “coercive philanthropy.” If experts can glean which way social betterment lies, who is the individual to object? The job of the economist is not to consider discrete questions about how to, say, maximize productivity or measure discretionary income. It is to fix society in all its relations, right down to each individual. The goal of the economist, Ely believed, was to hasten “the most perfect development of all human faculties in each individual.” Whether the individual wanted that development was irrelevant.

In this respect, Ely was one of the primary architects of the

transformation of liberalism from a doctrine of negative liberty (having

the state stay out of your way) into a doctrine of positive liberty

(having the state set you up with the tools and teaching necessary to

“be all you can be”). His goal was “to equalize opportunities” and to

give “to each the means for the development, complete and harmonious, of

all his faculties.” Regulating “industrial and other social relations

existing among men is a condition of freedom,” he wrote. To this end,

Ely advocated “industrial armies,” arguing that young men and society

alike would benefit from a form of civilian conscription straight into

the factories. If

implemented, his ideas might “lessen the amount of theoretical liberty,”

but would surely “increase control over nature in the individual, and

promote the growth of practical liberty.” That idea —

“practical liberty” — is the vision behind the “Economic Bill of Rights”

that FDR promulgated decades later, and echoes of it can be heard every

day in calls for a “new New Deal.”

But to discuss Ely

purely in terms of public policy leaves out his most important work: He

was, bar none, the most important lay proselytizer of the progressive

social gospel and “Christian socialism” in America. A

close friend or adviser to nearly every major social-gospel preacher, he

founded the “Christian sociology” movement. Ely scholar Benjamin Rader

reports that “ministers across the country used Ely’s writing as a basis

for sermons.” Ely’s Social Aspects of Christianity was a

definitive text. “For more than twenty years,” writes Rader, “every

minister entering the Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church was

required to read Social Aspects as well as Ely’s An Introduction to Political Economy.”

Ely was born in 1854 in western New York to pious Yankee and Puritan

Presbyterian parents. His father, Ezra, was an “extreme Sabbatarian,” to

use Murray Rothbard’s phrase, refusing to let his children even read or

play games on Sunday. In order to avoid working on the Sabbath, Ezra

quit his well-paying job as a civil engineer on the railroads and

struggled as a farmer. Despite needing the money, he refused to grow

barley — the best crop for his soil — because it could be used for the

devil’s brew, beer. While Ezra lamented that young Richard never had a

proper conversion experience to “become a good Presbyterian,” he

nonetheless imbued in Richard a religious commitment to egalitarianism

and a desire to “set the world on fire.”

This religious conviction animated Richard Ely, to the extent that he believed every aspect of life should have Christianity injected into it.

He held that Christians made a fundamental error by holding that

salvation lies in the next life. When Jesus says that his kingdom is

“not of this world,” the correct translation, according to Ely, is “not

of this age.” And it was Ely’s core conviction that the age of salvation

could be reached through the judicious application of welfare-state

policies. He wrote, in Aspects: “I take this as my thesis:

Christianity is primarily concerned with this world, and it is the

mission of Christianity to bring to pass here a kingdom of righteousness

and to rescue from the evil one and redeem all our social relations.” The

mating of his German historicism and American religion spawned a hybrid

offspring that recognized no significant distinction between “is” and

“ought,” because what exists now is merely the current installment of

God’s plan. “The ‘Is’ embraces the future ‘Ought,’” Ely

explained. “This in itself answers the question whether political

economists should deal merely with what is, or also with what ought to

be. The two cannot be separated.” The Christian doctrine of “service” became a divine injunction to advance a non-Marxist national socialism.

There was a great controversy over whether Ely was literally a

socialist. He played an interesting game in his early writings: on one

hand making an impassioned case for the inevitability and desirability

of socialism, while on the other insisting that he was not a socialist.

It’s a rhetorical pose that should be familiar today, as many liberals

speak glowingly of the benefits of social democracy and defend outright

socialist activists while insisting that they are not themselves

socialists. Ely’s posture didn’t convince everyone. Prompted by an

attack on Ely in The Nation, then a reliably laissez-faire

magazine, the University of Wisconsin conducted a major inquiry into the

charge that Ely was fomenting support for radicalism and violence. He

was ultimately cleared, though the experience rattled him. (It was

around this time that Teddy Roosevelt bumped into him and asked, “Hello,

Ely. Is The Nation still after you? No man can read The Nation and remain a gentleman.”)

It is a confusing

debate to follow now, because the term “socialism” has been so tainted

by just one, Marxist, variant of it. But socialism had a more nimble and

nuanced set of meanings a century ago. Ely rejected revolutionary,

non-Christian socialism on numerous grounds, including its Marxist faith

in abstract universal laws, its atheism, and its anarchic violence. He

favored instead a “golden mean” whereby a profoundly paternalistic state

intervened under the instruction of experts like himself, in the name

of guiding society toward ever greater

cooperation and the true

socialism of the Kingdom of Heaven.

Nonetheless, Ely invariably saw socialistic government programs as

the best means for realizing the Christian exhortation to live by the

golden rule. Ely was what some today would call a “Christianist,” subverting

Christianity into an explicitly political and programmatic doctrine

delineating how law, economics, business, and individual behavior should

be organized. He complained that contemporary life is

“divided into things sacred and things secular” and asserted that “to a

Christian all things must be sacred, his business as well as his

church.” The American Economic Association (which initially brimmed with

over 60 ministers as members) was to be a fundamentally religious

organization that imbued all of its analysis and recommendations with a

Christian vision that rejected laissez-faire economics as sinful and

cruel.

It should be no surprise that Ely was a statist par excellence.

Indeed, for Ely, the church was subsidiary to the state. Even the

nation, which for the historical school was the most basic political

unit and a galvanizing force for socialism, mattered less than the

state. If the nation was the body politic, the state was its soul, its

conscience, the divine spark of God’s will. “God

works through the State in carrying out His purposes more universally

than through any other institution,” Ely wrote. It “is religious in its

essence,” and “a mighty force in furthering God’s kingdom and

establishing righteous relations.” The only legitimate

reason to restrain the state’s right and authority to intervene in

society, according to Ely, lay in the limits of its “ability to do

good.” And since the state was the manifestation of God on earth, its

ability to do good was limitless.

Liberals often like to discuss the progressives and the social gospel

as distinct if occasionally overlapping phenomena. The truth was closer

to the opposite: Progressivism and the social gospel were usually the

same phenomena, and were only occasionally distinct from each other. The

social-gospel movement often retreated to the new economics (or to

eugenics) when it could not find sufficient arguments in scripture or

theology. And the new economists invoked Christianity whenever their

numbers didn’t add up. The corruption of both factions was nearly total.

The “philosopher Eric Voegelin famously warned againstimmanentizing the eschaton.”

The phrase’s exotic polysyllabicism was no doubt part of its appeal for

William F. Buckley Jr., who helped popularize it. To immanentize the

eschaton is to attempt to establish a Kingdom of Heaven on Earth. For

Voegelin, this Gnostic heresy was the underlying motive for all of the leftist isms of the 20th century. He once quipped that for the Marxist, “Christ the Redeemer is replaced by the steam engine as the promise of the realm to come.”

More than any other thinker, Ely introduced the drive to immanentize

the eschaton into the mainstream of progressive thinking, where it

remains today.

What united the

socialists, the progressives, the social gospellers, the pragmatists,

the nationalists, the fascists, the Marxists, and the other factions of

intellectuals who rallied at the wake of “God’s funeral” was the idea

that old ideas needed to be thrown away. These new intellectuals

insisted that the “crust of custom” — a popular phrase at the time,

coined by Walter Bagehot — had to be broken, and that the dogmas,

assumptions, rules, and habits associated with the old order had to be

either ignored or, better, destroyed. This was from the outset a

moralistic mission because, as they saw it, the old

notions of universal truths were created for the benefit of the greedy

haves in order to oppress the have-nots.

Such thinking led progressive historians such as Charles Beard to

argue that the U.S. Constitution was not so much a marvelous advance in

human liberty as an elaborate con constructed to protect the wealth of a

few landowners, and political scientists such as Woodrow Wilson to

argue that the written Constitution should be replaced with a living one

interpretable only by the new intelligentsia.

And here lies the

moral of the story. Ely’s determination to meld Christianity and

economics while claiming that science was always on his side undermined

the authority of Christianity while accelerating the growth and

increasing the power of the state. The “pragmatist

razor” that trims away needless superstition sliced away Christianity

whenever it got in the way of statist imperatives. With time, the state became the golden calf.

Some progressives came to recognize what they had done. Toward the

end of his life, after he had turned (quite viciously) on FDR, Charles

Beard observed of the New Deal progressives: “These people are talking

the relativism which will ruin liberalism yet. Don’t they know that the

means can make the ends? Don’t they realize that their method of arguing

can justify anything? I wish we could find some way of getting rid of conservative morality without having these youngsters drop all morality.” Nearly 20 years earlier, the progressive J. Allen Smith complained of Wilson-era progressives:

'The

real trouble with us reformers is that we made reform a crusade against

standards. Well, we smashed them all and now neither we nor anybody

else have anything left.'

____________________

John Dewey and the Philosophical Refounding of America

By Tiffany Jones Miller

The “progressive” label is back in vogue; politicians of the Left routinely use it to describe themselves, hoping to avoid the radical connotations associated with being “liberal” in the post-Reagan era. The irony in this is manifold, especially because the aim of the movement to which the name refers, the late-19th- and early-20th-century progressive movement, was anything but moderate.

If the progressive label seems less radical today, it is only because progressivism is less well known than its liberal progeny. It was initially an academic phenomenon far removed from American politics. Particularly in the post–Civil War American university, professors — many of whom had obtained their graduate training in German universities, and whose thought reflected the “intoxicating effect of the undiluted Hegelian philosophy upon the American mind,” as progressive Charles Merriam once put it — articulated a critique of America that was as deep as it was wide. It began with a conscious rejection of the natural-rights principles of the American founding and the promotion of a new understanding of freedom, history, and the state in their stead. From this foundation, the progressives then criticized virtually every aspect of our traditional way of life, recommending reforms or “social reorganization” on a sweeping scale, the primary engine of which was to be a new, “positive” role for the state. As the progressives’ influence in the academy increased, and growing numbers of their students sallied forth into all aspects of endeavor, this intellectual transformation gradually began to reshape the broader American mind, and, in time, American political practice. “A new regime in thought,” as Eldon Eisenach writes, “began to become a new regime in power.”

While many progressive academics helped effect this philosophical transformation, few, if any, were as influential as Dewey. Through an immense and wide-ranging body of work, vigorous activism, and his many students, Dewey’s mark was deep and enduring. Part of the reason for this was that he enjoyed an unusualy long and prolific academic career. In 1884, Dewey received his doctorate from Johns Hopkins University, that seedbed of progressive academia where — as Jonah Goldberg explains elsewhere in this issue — Richard T. Ely taught economics and helped cultivate future reformers like Woodrow Wilson, John R. Commons, and Frederic Howe. Over the course of his subsequent half-century career, Dewey taught mainly at the University of Chicago and Columbia University, where he held appointments in both philosophy and education, and published over 40 books and several hundred articles. In 1914, moreover, Dewey became a regular contributor to Herbert Croly’s New Republic, the flagship journal of progressivism; he also played a more or less important role in the formation of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, the American Civil Liberties Union, and the American Federation of Teachers. During the New Deal, Dewey and his students helped shape the character of various programs, including the fine-arts program of the Works Progress Administration and the flagrantly socialist community-building program undertaken by the Division of Subsistence Homesteads. Dewey’s social theory continued to influence major political events even after his death in 1952. President Johnson not only delivered many speeches (including his signature Great Society address) that read, as James Ceaser has aptly noted, like “a grammar school version of some of John Dewey’s writings,” but professed his admiration for “Dr. Johnny.”

Finally, Dewey arguably did more than any other reformer to repackage progressive social theory in a way that obscured just how radically its principles departed from those of the American founding. Like Ely and many of his fellow progressive academics, Dewey initially embraced the term “socialism” to describe his social theory. Only after realizing how damaging the name was to the socialist cause did he, like other progressives, begin to avoid it. In the early 1930s, accordingly, Dewey begged the Socialist party, of which he was a longtime member, to change its name. “The greatest handicap from which special measures favored by the Socialists suffer,” Dewey declared, “is that they are advanced by the Socialist party as Socialism. The prejudice against the name may be a regrettable prejudice but its influence is so powerful that it is much more reasonable to imagine all but the most dogmatic Socialists joining a new party than to imagine any considerable part of the American people going over to them.”

Dewey’s influential 1935 tract, Liberalism and Social Action, should be read in light of this conclusion. In this essay, Dewey purportedly recounts the “history of liberalism.” “Liberalism,” he suggests, is a social theory defined by a commitment to certain “enduring,” fundamental principles, such as liberty and individualism. After defining these principles in the progressives’ terms — e.g. liberty means the “claim of every individual to the full development of his capacities” — Dewey claims that the American founders, no less than the progressives, were committed to them. By seemingly establishing the agreement of the two groups, Dewey is able to dismiss their disagreement over the proper scope of government as a mere disagreement over the best “means” of securing their common “ends.” That is, although limited government may once have been the best means of securing individual liberty, its perpetuation in the changed social and economic circumstances of the 20th century would simply ensure liberty’s denial. If contemporary defenders of limited government only realized this, he concludes, they would drop their commitment to limited government and enthusiastically join their fellow “liberals” in expanding the power of the state. Dewey’s argument has enjoyed a potent legacy in subsequent scholarship, blinding many to what he and his fellow progressives plainly understood: however superficially similar, the founders’ conception of freedom, and the way of living to which it gave rise, differs markedly from the progressive conception of freedom and the more wholly “social” way of living that follows from it.

Commentators tend to underplay Dewey’s connection to the philosophical taproot of the wider progressive movement. Much attention is given to his role, along with William James, in founding pragmatism, a philosophical school frequently described as uniquely American. Dewey’s turn to pragmatism is admittedly important, as it helped induce the development of the increasingly relativistic outlook so characteristic of contemporary liberalism. Nevertheless, such an account of his thought is both incomplete and overstated. Indeed, when he was a graduate student at Hopkins and in the early years of his career, Dewey’s thought, like that of his fellow progressives generally, was decidedly Hegelian. Even after turning away from Hegelian metaphysics, Dewey retained a significant Hegelian residual. In 1945, less than a decade before his death, he declared: “I jumped through Hegel, I should say, not just out of him. I took some of the hoop . . . with me, and also carried away considerable of the paper the hoop was filled with.” Dewey’s break with Hegel was thus only partial, and did not essentially alter the content of the social theory he had developed while under Hegel’s spell.

The cornerstone of this theory — the principle from which “Dr. Johnny’s” diagnosis of America’s shortcomings, and his prescription for its reform, proceeds — is a new, “positive” conception of human freedom. Like Hegel, Dewey distinguishes between the “material” and “spiritual” aspects of human nature, and ranks the latter higher than the former. “The appetites and instincts may be ‘natural,’ in the sense that they are the beginning,” he explains in a 1908 text co-authored with James Tufts, but “the mental and spiritual life is ‘natural,’ as Aristotle puts it, in the sense that man’s full nature is developed only in such a life.” Although man’s instincts are natural in the sense of being spontaneous, man’s “mental and spiritual life is ‘natural’” in a different and higher sense — a teleological one. Like his instincts, man’s spiritual faculties exist in him from the beginning; unlike his instincts, however, they exist only in potential, in an inactive or undeveloped way. Man thus “cannot be all that he may be,” cannot realize his “full nature” and thereby achieve his “best life,” until he is able to develop his higher faculties properly and subordinate his lower nature to their rule — to the resulting “world of ideal interests.” A man so developed, the early Dewey declares, would be “perfect.” In short, for Dewey, as for Hegel, because individuals can become free only to the extent that they actualize their spiritual potential, true freedom is “something to be achieved.”

In the early years of his career, accordingly, Dewey’s socialism was grounded on a conception of human freedom synonymous with the realization or fulfillment of spiritual potential. (Even after his turn to pragmatism, interestingly, he continued to use this teleological nomenclature, however vigorously he denied the metaphysics from which it was derived.) Man’s spiritual potential, while encompassing a host of faculties or talents that vary among individuals, also, and more essentially, consists in “capacities” common to all men, especially his social, intellectual, and aesthetic ones. Of these, man’s social capacity is particularly significant. For Dewey, its development involves a process through which the individual’s will becomes decreasingly determined by his particular interests and increasingly concerned with the “interests of others.” Not only are these interests defined ultimately in terms of comprehensive good (or spiritual welfare), but these “others” ultimately include all human beings. As the individual grows more social, he will increasingly choose to promote the “fullest life” for every other human being in every sphere of life, e.g. in business and government (domestically and internationally) no less than in family and church.

In the founders’ view, by contrast, the natural rights of the individual correspond to a series of natural duties, the scope of which vary with the social relationship in question. Thus, while parents are obliged to promote the comprehensive good or welfare of their children, and to sacrifice their personal concerns accordingly, the obligations they owe unrelated adults are far more minimal — e.g. to refrain from interfering with their freedom, to honor contracts with them, and, at the outside, to promote their (mere) preservation. Beyond these duties, individuals are entitled to pursue their own concerns, a right that government, in turn, is obliged to respect. While individuals are free to assume a more robust obligation to unrelated others, as through a church, government itself is not the agent for advancing it.

From Dewey’s (and the progressives’) standpoint, so minimal an understanding of obligation allows men to pursue a degree of selfishness that is developmentally primitive and hence morally disgusting. The progressives’ view on this matter is particularly obvious in the scorn they heap upon the free market, an economic system animated by the selfish, and hence base, profit motive, but they viewed virtually every aspect of life in America — e.g. the prevailing interpretation of Christian Scripture and worship of God, the aim and methods of education, the physical layout and architecture of our cities and towns, the pattern of rural settlement and the character of life within it, the use of our natural resources, etc. — in the same light. The way of living inherited from the American founding was, in short, a cesspool of selfishness.

When freedom is redefined in terms of spiritual fulfillment, the “problem of achieving freedom” radically changes. Freedom is no longer secured by constraining government interference with “the liberty of individuals in matters of conscience and economic action,” as Dewey notes, but rather by “establishing an entire social order, possessed of a spiritual authority that would nurture and direct the inner as well as the outer life of individuals.” The problem with limited government — with a government dedicated to securing the natural rights of man — is that it does not perform the more positive role of “nurtur[ing] and direct[ing]” the spiritual lives of the governed. Rather, it secures mere “negative freedom.” “Negative freedom,” Dewey clarifies, is “freedom from subjection to the will and control of others . . . capacity to act without being exposed to direct obstructions or interferences from others.” In practice, freedom understood as natural rights is “negative” because government puts individuals in the enjoyment of their rights (e.g. the right to acquire and use one’s property, to speak, to worship God according to the dictates of one’s conscience, etc.), primarily by restraining others — and, importantly, itself — from interfering with the individual’s right to make such decisions. While interference with individual decision-making is certainly not altogether illegitimate in a limited government, freedom is the normal case and restraint the exception.

At best, Dewey argues, such a government secures to every individual the mere legal right to realize his spiritual potential, a right that for many is essentially worthless. “The freedom of an agent who is merely released from direct external obstructions is formal and empty,” for unless he possesses every resource needed to take advantage of this broad legal opening, he will remain unable to exercise his freedom and thereby actualize his spiritual potential. While the law would “exempt [him] from interference in travel, in reading, in hearing music, in pursuing scientific research[,] . . . if he has neither material means nor mental cultivation to enjoy these legal possibilities, mere exemption means little or nothing.” In view of this situation, the perpetuation of limited government would consign many, perhaps most, Americans to a condition of spiritual retardation.

If mere negative freedom is to be transformed into what Dewey calls “effective” freedom, accordingly, negative government must give way to positive government. That is, the legislative power of government must expand in whatever ways are needed — and hence however far proves necessary — to effect a wider and deeper distribution of the resources essential to the actualization of every American’s spiritual potential. As Dewey presents it, and as subsequent political practice confirmed, this process is basically synonymous with the implementation of the positive conception of individual rights. In this new order, individuals are entitled to whatever resources they need to attain spiritual fulfillment. Because Dewey, like the progressives generally, regarded poverty as among the greatest constraints on spiritual development, a host of the new rights purported to enhance the material security of poorer Americans — e.g. the right to a job, a minimum wage, a maximum work day and week, a decent home (public housing), and insurance against accident (workers’ compensation), illness (public health care), and old age (Social Security). Most of these rights were enshrined in federal law during the New Deal. Because access to education at all levels and to fine art are no less essential to spiritual fulfillment, Dewey also advocated generous public provision of these resources — and indeed the provision of both was a hallmark of LBJ’s Great Society. Because all such resources are secured for those who lack them through the creation of new redistributive programs (which increase the burden on those who pay taxes) and the imposition of new regulations such as the minimum wage (which foreclose choices previously reserved to the individual), a politics of rights-as-resources inevitably erodes freedom in the founders’ sense.

In sum, the core of Dewey’s progressivism, socialism, or what subsequently became known (thanks in no small part to his efforts) as liberalism, is freedom understood as spiritual fulfillment. Because the embrace of this ideal necessitated a thoroughgoing reconstruction of the American way of living, primarily by means of the positive state, it revolutionized not only the founders’ theory of limited government, but also their constitutionalism: for, as Dewey and Tufts candidly note, progressive judges have “smuggled in” many valuable reforms by devising “‘legal fictions’ and by interpretations which have stretched the original text to uses undreamed of.” Dewey was hardly alone in encouraging this transformation, but few would deny the preeminent role he played in it.

____________________

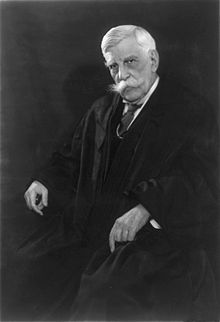

The Curious Constitution of Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr.

By Bradley C. S. Watson

Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. was appointed to the U.S. Supreme Court by Theodore Roosevelt, America’s first progressive president. He served from 1902 to 1932, and his name remains familiar to this day. There is good reason for that, as Holmes stands out among Supreme Court justices for his enduring influence on constitutional jurisprudence.

Holmes set forth the essence of progressivism as a legal theory, though he was not primarily a theorist. Instead, he was a practitioner, so we must distill from his many arguments and judgments a coherent account of progressivism as a distinctly legal — as opposed to philosophical or political — movement (though it was certainly all three of these things). The legal aspect is important, because by the middle part of the 20th century, it was clear that the judicial branch of government was the one that would carry progressive ideology forward in the most comprehensive manner.

Holmes was heir to, and an exponent of, doctrines that permeated American intellectual circles during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. These doctrines were offshoots of the era’s new “scientific” attitudes toward politics and human affairs. After the Civil War, Social Darwinism and pragmatism came to dominate the American intellectual landscape, sweeping away all notions of politics grounded in moral truths; in legal circles, they spawned a version of constitutionalism dedicated to their defense. By the early 20th century, the two doctrines had merged to form the compact and powerful ideology of progressivism.

For both pragmatists and Social Darwinists, life and thought are directed to continuous change, experimentation, and adaptation. The test of the worthiness of any proposition is not its truth in and of itself — a truth grounded in the nature of things — but its adaptive success (“survival of the fittest”). This process of endless change and adaptation is the engine of progress. Although Holmes is often depicted as an advocate of “judicial restraint,” he saw the need for courts to provide creative responses dictated by the times. And for progressives, the times are always a-changin’.

For Holmes, law and society are forever in flux, and courts adjudicate mainly with an eye to the law’s practical effects. For this reason, Holmes led the charge to eradicate judicial reasoning that was based on principles of natural law or natural rights. Morality, he felt, has nothing to do with the law; it amounts to no more than a state of mind. There are no objective standards for determining right and wrong, and therefore no “just” or “constitutional” answers to legal questions. Legal adjudication has no principled basis; instead it comes down to weighing questions of social advantage according to the exigencies of the age.

Holmes’s view raises a fundamental question: If the Constitution does not dictate anything timeless and enduring, is there any ground for faith in the Constitution itself, or in classical-liberal constitutionalist?

Such a constitutionalism, after all, would seem to require an understanding that only known and promulgated laws, whose meaning is stable over time, can bind citizens. Yet Holmesian “legal realism” denies the very possibility of such laws.

In a 1915 essay, Holmes writes:

“When I say that a thing is true, I

mean that I cannot help believing it. . . . But as there are many things

that I cannot help doing that the universe can, I do not venture to

assume that my inabilities in the way of thought are inabilities of the

universe. I therefore define the truth as the system of my limitations.”

Even more radically, Holmes’s efforts to debunk the philosopher’s quest for “absolute” truth or the jurist’s quest for “natural law” lead him to suggest that the morality of even the greatest human struggles depends entirely on the outcome. In a 1918 essay titled “Natural Law,” Holmes writes: 'I used to say, when I was young, that truth was the majority vote of that nation that could lick all others. Certainly we may expect that the received opinion about the present war [i.e., World War I] will depend a good deal upon which side wins (I hope with all my soul it will be mine), and I think that the statement was correct in so far as it implied that our test of truth is a reference to either a present or an imagined future majority in favor of our view.'

This account reduces what is called “natural law” to an inexorable process of historical unfolding and paints it as nothing more than a dominant opinion. Holmes thereby lays the foundation for a judicial seeking-out and support of such dominant opinions (even, it turns out, if they begin in foreign lands putatively more advanced than our own) and, concomitantly, a judicial aversion to “weaker” opinions or entities that appear not to support the strength and growth of the social organism.

When Holmes dismisses traditional concepts of natural law, his jurisprudence becomes merely a predictive tool along the lines of modern science. Well-trained lawyers, according to Holmes, become the oracles of the new legalism and indeed the new constitutionalism. To know legal dogma is to be able to make predictions. Under Holmes’s definition of truth as that which is strongest or most useful in the here and now, it is beyond lawyers’ ability — or anyone’s — to point to the “constitutional” truth of things; the concept has no meaning.

In an influential 1897 essay titled “The Path of the Law,” Holmes writes: “People want to know under what circumstances and how far they will run the risk of coming against what is so much stronger than themselves, and hence it becomes a business to find out when this danger is to be feared. The object of our study, then, is prediction, the prediction of the incidence of public force through the instrumentality of the courts.” Such a claim is in significant tension with the understandings of law at the heart of the Western intellectual tradition. It is very far from Plato’s notion that law seeks to be a discovery of what is, or Thomas Aquinas’s notion that proper human law must not conflict with natural law, which is accessible to unaided human reason. It is also very far from the American founders’ written constitutionalism, which was designed to protect the God-given natural rights of equal political beings.

In what terms are we to understand what the law’s instrumentality — the courts — will actually do? Holmes claims that law reflects not logic but experience. Law cannot be understood to be syllogistic, with the major premise of sound legal analysis being found in the law itself and the minor premise in the facts of the case. If it could, then judges would be able to decide cases on the basis of right reason. Instead, judges must look to history and incorporate science — especially economic science — into their jurisprudence. Holmes’s Social Darwinism is exhibited in his view that judges express the wishes of their class at a particular historical point. The content and growth of the law are determined as much by organic “forces” as by men.

The actual grounds of decision, according to Holmes, are based on the “felt necessities” of the time: Judges decide questions first and find reasons for them ex post facto. There can thus be no logical necessity or reasoning about law, apart from calculations dictated by answers to questions of socioeconomic advantage. Holmes maintains that one of the problems of the common law prior to legal realism was that it had not been, in a certain sense, theoretical enough, i.e., not reliant enough on utilitarian social and economic theory, as opposed to insights into eternal questions of justice. In fact, he writes in “The Path of the Law”

''that a judge gives his conclusions “because of some belief as to the practice of the community or of a class, or because of some opinion as to policy. . . . Such matters really are battle grounds where the means do not exist for the determinations that shall be good for all time, and where the decision can do no more than embody the preference of a given body in a given time and place. . . . Our law is open to reconsideration upon a slight change in the habit of the public mind. No concrete proposition is self-evident.”

The core of Holmes’s legal realism — its pragmatism along with a confidence in, or grim acceptance of, the progress of History — is brought into relief by examining its insistence that courts must interpret and balance rights. The importance of this judicial balancing is nowhere more evident than in Holmes’s free-speech jurisprudence. In Schenck v. United States (1919), Holmes stated the famous “clear and present danger” test as a pragmatic doctrine that avoids inquiry into the content (that is, the nature) of speech and concentrates only on its likely effects. Prior to the articulation of this doctrine, the content of speech was considered of vital constitutional import.

In Abrams v. United States (1919) — decided just months after Schenck — a majority of the Court upheld the convictions of anti-government, anti-war radicals who advocated violence. Holmes dissented on the basis of his “clear and present danger” test. According to Holmes, free speech fosters free trade in ideas, and the test of “truth” is its ability to get accepted in the marketplace of ideas, which will happen when the market assesses its needs. Implicit in this is a Darwinian confidence that society need not fear that which triumphs. The beliefs that will triumph in the long run are what is critical — not the constitutional or regime beliefs that have existed up to the present, much less a timeless natural law.

For Holmes, rights are willed by the dominant forces of an age and community. Whatever prevails is right; therefore all political developments are good util they are no longer ascendant, and every regime is worthy until it crumbles or is overthrown. Judges and legislators must to some large degree reflect dominant forces according to the state’s position in History, with a capital H — that is to say, history understood not as a mere record of events, but as an inexorable process that dictates its own moral categories. Holmes was therefore a progressive in this Historical sense, rather than in his individual judgments, which could readily favor repressive measures. Holmes’s thought can be said to reduce to a new “natural” law — i.e., a Darwinian process of triumph over lesser forms, or progressivism as legal theory.

In Gitlow v. New York (1925), Holmes makes this claim:

“If in the long run the beliefs expressed in proletarian

dictatorship are destined to be accepted by the dominant forces of the

community, the only meaning of free speech is that they should be given

their chance and have their way.”

Yet if, as Holmes asserts, the Constitution is itself neutral or indifferent on this question, what is the basis for his constitutional ruling in favor of a First Amendment claim? Again, we are led to Darwinian experimentalism, albeit of a foreboding, fatalistic kind.

Holmes was often willing to show great deference to legislative judgments as the sovereign expressions of popular will. In Lochner v. New York (1905), Holmes dissented (on the grounds of constitutional neutrality) from a majority that held that state economic regulations limiting work hours were unconstitutional. He famously claimed:

“I strongly believe

that my agreement or disagreement has nothing to do with the right of a

majority to embody their opinions in law. . . . I think the word liberty

in the Fourteenth Amendment is perverted when it is held to prevent the

natural outcome of a dominant opinion.”

But this modest conception of the judicial function in a democracy was not Holmes’s final word. Holmes’s jurisprudence suggests that the Supreme Court should intervene where the legislative branch limits free speech, but not where it limits economic freedom. For Holmes, survival or progress might require activism or restraint, and reliance on either is purely an instrumental — or experimental — question.

Racial improvement through eugenics was one outgrowth of early-20th-century progressivism, which placed considerable faith in the ability of science and purportedly scientific administration to solve social problems. In one of his most notorious judgments, Holmes wrote the 8-to-1 majority opinion in Buck v. Bell (1927), which upheld Virginia’s compulsory-sterilization law. Holmes upheld the law on the grounds that those targeted by it were treated with scrupulous procedural fairness. Decrying those who “sap the strength” of society, and contending, in reference to the affected litigant nd her family, that “three generations of imbeciles are enough,” Holmes seemed to accept the eugenic arguments to the point of endorsing them on grounds of public policy. He reasoned by analogy, comparing the hardships of sterilization with the sacrifices of soldiers in battle. Referring to the Civil War, he argued that if “the public welfare may call upon the best citizens for their lives,” surely those who sap the strength of the state could be called upon for a lesser sacrifice.

Following in Holmes’s footsteps, a long line of progressive jurists have broken with the founders’ Constitution — and with it, the very notion that human beings are creatures of a certain type, with transcendent purposes that do not change over time. In his rejection of natural law and natural rights — and thus of a classical liberal constitutionalism with limited state power — Holmes laid the groundwork for the contemporary era of jurisprudence, in which judges look to their visions of the future more than to the documents and doctrines of the past, and take on a new and far more active role in the constitutional order. The retrospective conception of the law — common or constitutional — hangs today by a bare thread.

There is a residual incoherence to the progressive jurisprudence that has followed Holmes. It alternates between two poles. On one hand, it expresses the desire to make decisions that are legitimate in the eyes of the community — decisions that respond to something like, in Holmes’s words, the “felt necessities” of the age. On the other, it encourages decisions that oppose what it claims is illegitimate majority will. But neither pole is rooted in constitutional text, tradition, logic, or structure. Rather, they are both rooted in the judge’s view of which necessities are most deeply felt and most likely to encourage social and personal growth. The practical result, in contemporary jurisprudence, is that art trumps economics, expression trumps the common good, subjectivity trumps morality, freedom trumps natural law, and will trumps deliberation. Such is the face of progressive jurisprudence, a face that now seems tremendously weather-beaten from its triumphal march of a hundred years’ duration.

Having rooted itself so firmly in the historicist thought that guides America and — under different names — the Western world as a whole, and having gained so much strength and momentum on its virtually uninterrupted path, this jurisprudence will not be displaced anytime soon. Its success is marked by the fact that it no longer seeks victory, only legitimation in a constitutional order that is still at odds with it.

____________________

Herbert Croly’s American Bismarcks

By Fred Seigel

Herbert Croly’s 1909 book The Promise of American Life, the ur-text of pre–World War I progressivism, was still essential reading for 1960s college students. In 1965 alone, the book was reprinted by three major publishers, each featuring a new introduction by a prominent liberal historian (in one case, Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr.). Students were, at the best schools, taught in the days of the Great Society to see The Promise not only as the founding document of modern American liberalism — and a prophecy of the New Deal — but also as a charter empowering them to become the country’s future political and cultural leaders.

Croly’s book taught students that the growth of government could best be understood as the natural expression of the underlying forces of American history. The book’s most famous argument was that through progressivism America could achieve its rendezvous with destiny by applying “Hamiltonian means” — that is, the power of a strong central government — to achieve “Jeffersonian ends” — namely, the enhancement of individual freedom.

The problem with this catchy formulation is that, while Croly is indeed the first founding father of modern liberalism, he had little use for Hamilton’s ideal of a commercial republic and even less for Jefferson’s yeoman individualists; they were the bêtes noires of his writing.

Croly had studied in Paris and had, in the words of his friend, the literary critic Edmund Wilson, “an addiction to French political philosophy”; Wilson also said that Croly “considered his culture mainly French.” Croly’s aim was to refound the republic on a Francophile footing. His argument in The Promise and its successor, Progressive Democracy (1915), two books so tightly connected that Croly said that he wished he had written them as one, is best described as a plan for achieving (Auguste) Comtean ends — that is, the worship of society — by Rousseauean means — i.e., a plebiscitary democracy led by enlightened experts. As Croly himself explained it, he was “applying ideas, long familiar to foreign political thinkers, to the subject matter of American life.”

If liberals have a hard time understanding their own history, that’s true in part because they’ve so successfully avoided dealing with who Herbert Croly was and what he hoped to achieve.

Croly’s moralistic streak led his detractors to describe him as “Crolier than thou,” but it was an unconventional kind of morality. He was born in 1869 to David Croly and Jane Cunningham Croly, both successful New York journalists. David Croly, a sexual reformer who believed that copulatory repression bred social disorder, was a founding member of the Church of Humanity, an institution dedicated to propagating the ideas of the French sociologist Auguste Comte. His wife, known professionally as “Jennie June,” was a caustic critic of marriage and a leading feminist writer. Their son was among the first in America to be baptized into the Comtean faith. Comte, a utopian socialist of sorts, attributed the troubles of the modern world to the “spiritual disorganization of society.” He wanted to deploy positivist science to restore the unity lost to the Protestant Reformation, and thus create a modern version of the “moral communism of medieval Christendom.”

The young Herbert Croly was raised to be a prodigy but developed slowly. He left Harvard before graduating and he wrote for the Architectural Record until, at the age of 40, he produced The Promise of American Life. The book sold poorly but propelled him onto the national stage, where he drew the interest of former president Theodore Roosevelt. Croly would influence TR just as TR, whom Croly saw as a sort of American Bismarck, had already influenced him.

Bismarck was much on Croly’s mind. In The Promise, Croly showed nothing but contempt for English liberalism. He saw it leading to “economic individualism . . . faith in compromise . . . and a dread of ideas.” These had, he wrote, made “the English system a hopelessly confused bundle of semi-efficiency and semi-inefficiency.” Croly much preferred the greater efficiency and, as he saw it, the greater equality of Germany, where “little by little the fertile seed of Bismarck’s Prussian patriotism grew into a German semi-democratic nationalism.” Its great virtue was organization: “In every direction,” he wrote, “German activity was organized and was placed under skilled professional leadership, while . . . each of these special lines of work was subordinated to its particular place in a comprehensive scheme of national economy. The upshot increased security, happiness and opportunity for development for the whole German people.”

Croly saw economic inequality in America as an expression of an industrial capitalism born of economic individualism that needed to be rectified by state action. This view was incorporated into the liberal canon. Similarly, liberals came to accept as a given his insistence that, in America, the German path could be achieved only by using higher education to create the “skilled professional leadership” needed to run society. Entrusting public affairs to this educated class would, Croly believed, have “a leavening effect on human nature.” “Democracy,” he said, “must stand or fall on a platform of possible human perfectibility.” These were the words of a radical, not a reformer — a man who, like Marx and Comte, saw himself as leading humanity to a higher and more refined stage of civilization.

Croly believed businessmen and their allies — the jack-of-all-trades latter-day Jeffersonians — were blocking the path to the bright future he envisioned for the specialists of the rising professional classes. America’s business culture threatened individuality, he insisted, because businessmen, despite their differences, “have a way of becoming fundamentally very much alike. Their individualities are forced into a common mold because the ultimate measure of the value of their work is the same, and is nothing but its results in cash. . . . In so far as te economic motive prevails, individuality is not developed, it is stifled.”

The flip side of Croly’s hostility to self-interested businessmen was his adoration of the new class of intellectuals and artists emerging in America. This class had the virtue, he insisted, of a “disinterested” take on public affairs, which allowed it to rise above the petty peculiarities of the marketplace in order to serve all of humanity, in the manner of Plato’s guardians. But Croly complained that “the popular interest in the Higher Education has not served to make Americans attach much importance to the advice of the highly educated man. He is less of a practical power in the United States than he is in any European country.” Like H. G. Wells in England, Mussolini in Italy, and Lenin in Russia, Croly wanted the collective power of society put “at the service of its ablest members,” who would be given the lead roles in the drama of social re-creation.

Croly’s progressive-era audience was stirred by his insistence that the “ablest” deserved a more interesting world. “The opportunities, which during the past few years the reformers have enjoyed to make their personal lives more interesting, would be nothing compared to the opportunities for all sorts of stirring and responsible work, which would be demanded of individuals under the proposed plan for political and economic reorganization.”

The Promise closes with Croly promising that “the common citizen can become something of a saint and something of a hero, not by growing to heroic portions in his own person, but by the sincere and enthusiastic imitation of heroes and saints.” This will depend, he argues in the closing sentence, on “the ability of his exceptional fellow-countrymen to offer him acceptable examples of heroism and saintliness.” Croly’s critique of industrial inequality had by its conclusion become a call for, in his own words, the “creation of a political, economic, and social aristocracy.”

Croly played an important role in the extraordinary presidential election of 1912, in which the incumbent, Republican regular William Howard Taft, was challenged not only by his predecessor, Teddy Roosevelt, but also by Democrat Woodrow Wilson and by Socialist Eugene V. Debs. Not since the days of the founding fathers had so much candlepower been deployed in the pursuit of public office. Croly successfully took it upon himself to articulate Roosevelt’s New Nationalist creed in opposition to what he saw as the neo-Jeffersonianism of Wilson’s “New Freedom,” as articulated by Louis Brandeis.

Caught up in the then-leftward drift of the country, Croly reframed his earlier argument in a new book, Progressive Democracy. In The Promise, Croly’s target had been the Jeffersonian ideal as exemplified by its latter-day exponent, the populist William Jennings Bryan; in the important but far less influential Progressive Democracy, the object of his ire was the Constitution. Constitution worship, he argued, had produced “the monarchy of the Word.” Its legalistic constraints had become the enemy of Croly’s version of democracy, which he saw embodied in the syndicalist promise of the Industrial Workers of the World.

Croly hoped to see geographic representation, with its accompanying two-party system, replaced by syndicalist-style functional representation. In Croly’s ideal, government would not be built around states (which would be dissolved into the federal authority) but organized in terms of “associations of businessmen, of farmers, and of wage earners . . . of civic societies, voters’ leagues, ballot associations, women’s suffrage unions, single tax clubs and the like.” Croly’s goal has, in fact, been partly achieved, helping to cause the current fiscal crises of the deep-blue states. In California and New York, for instance, politics has been partly syndicalized, with virtual representation by racial interest groups and the public-sector unions to a degree displacing the old moderating ideal of geographic representation, under which a variety of interests had to be considered.

In Croly’s scheme, echoes of which can still be heard in demands to abolish the Electoral College, local parties and their bosses would be bypassed through plebiscitary democracy based on the ballot-initiative, referendum, and recall processes, with power concentrated in the hands of the national executive. The executive, in turn, would govern through commissions staffed by experts — an idea that endures in Obamacare.

Returning to Charles Fourier’s themes of sexual liberation, which had intrigued his father, Croly launched an attack on the old ideal of self-restraint. “Modern psychology,” he insisted, “affords no sufficient excuse for a morality of repression.” Social education “should seek primarily to release and develop rather than to dam up the instinctive sources of action in human nature.”

Drawing on the 19th-century utopian socialists while anticipating both the bohemian culture of the 1920s and the later hopes of the ’68ers, Croly argued that the growth of material wealth freed individuals to define themselves by their leisure activities. “The social culture itself will partake rather of the nature of play. . . . It might make every woman into something of a novelist and every man into something of a playwright.” Each would be able to pursue his own objective while maintaining the well-being of the organic whole, he argued, because “the progressive democratic faith . . . finds its consummation in a love . . . which is at bottom a spiritual expression of the mystical unity of human nature.”

Croly, a soft-voiced, preternaturally shy man, founded The New Republic in 1914 to serve as the voice of enlightened statism. By this time the Wilson administration had turned in Croly’s direction, and Croly had transferred his hero worship from Teddy Roosevelt to the once-reviled Princeton professor sitting in the White House. TNR under Croly’s leadership gathered a brilliant band of young writers, including Walter Lippmann, Walter Weyl, and Randolph Bourne. The last broke bitterly with Croly and TNR when the magazine backed Wilson’s reluctant entry into WWI. The Germanophile Bourne accused Croly of criminal naïveté in thinking that the war might be turned to progressive purposes. And when the fighting ended with a disappointing peace in Europe, combined with repression and Prohibition at home, Croly was a broken man.

In the early 1920s, a depressed Croly turned away from his deep involvement in politics and returned to his Comtean roots. He wrote of his despair in “The Breach in Civilization,” a manuscript that he withdrew from publication at the last moment. It argues that the subjectivism of the Protestant Reformation was the source of the world’s ills: The “materialism and individualism” of the modern world, he wrote, thrived “at the expense of a unified authoritative moral system.” And that, he says, produced a disaster: “the fumbling experiment . . . of an essentially secular civilization.”

Herbert Croly’s 1909 book The Promise of American Life, the ur-text of pre–World War I progressivism, was still essential reading for 1960s college students. In 1965 alone, the book was reprinted by three major publishers, each featuring a new introduction by a prominent liberal historian (in one case, Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr.). Students were, at the best schools, taught in the days of the Great Society to see The Promise not only as the founding document of modern American liberalism — and a prophecy of the New Deal — but also as a charter empowering them to become the country’s future political and cultural leaders.

Croly’s book taught students that the growth of government could best be understood as the natural expression of the underlying forces of American history. The book’s most famous argument was that through progressivism America could achieve its rendezvous with destiny by applying “Hamiltonian means” — that is, the power of a strong central government — to achieve “Jeffersonian ends” — namely, the enhancement of individual freedom.

The problem with this catchy formulation is that, while Croly is indeed the first founding father of modern liberalism, he had little use for Hamilton’s ideal of a commercial republic and even less for Jefferson’s yeoman individualists; they were the bêtes noires of his writing.

“To achieve a better future,” he argued, Americans had to be “emancipate[d] from their past.”

Croly had studied in Paris and had, in the words of his friend, the literary critic Edmund Wilson, “an addiction to French political philosophy”; Wilson also said that Croly “considered his culture mainly French.” Croly’s aim was to refound the republic on a Francophile footing. His argument in The Promise and its successor, Progressive Democracy (1915), two books so tightly connected that Croly said that he wished he had written them as one, is best described as a plan for achieving (Auguste) Comtean ends — that is, the worship of society — by Rousseauean means — i.e., a plebiscitary democracy led by enlightened experts. As Croly himself explained it, he was “applying ideas, long familiar to foreign political thinkers, to the subject matter of American life.”

If liberals have a hard time understanding their own history, that’s true in part because they’ve so successfully avoided dealing with who Herbert Croly was and what he hoped to achieve.

Croly’s moralistic streak led his detractors to describe him as “Crolier than thou,” but it was an unconventional kind of morality. He was born in 1869 to David Croly and Jane Cunningham Croly, both successful New York journalists. David Croly, a sexual reformer who believed that copulatory repression bred social disorder, was a founding member of the Church of Humanity, an institution dedicated to propagating the ideas of the French sociologist Auguste Comte. His wife, known professionally as “Jennie June,” was a caustic critic of marriage and a leading feminist writer. Their son was among the first in America to be baptized into the Comtean faith. Comte, a utopian socialist of sorts, attributed the troubles of the modern world to the “spiritual disorganization of society.” He wanted to deploy positivist science to restore the unity lost to the Protestant Reformation, and thus create a modern version of the “moral communism of medieval Christendom.”

The young Herbert Croly was raised to be a prodigy but developed slowly. He left Harvard before graduating and he wrote for the Architectural Record until, at the age of 40, he produced The Promise of American Life. The book sold poorly but propelled him onto the national stage, where he drew the interest of former president Theodore Roosevelt. Croly would influence TR just as TR, whom Croly saw as a sort of American Bismarck, had already influenced him.

Bismarck was much on Croly’s mind. In The Promise, Croly showed nothing but contempt for English liberalism. He saw it leading to “economic individualism . . . faith in compromise . . . and a dread of ideas.” These had, he wrote, made “the English system a hopelessly confused bundle of semi-efficiency and semi-inefficiency.” Croly much preferred the greater efficiency and, as he saw it, the greater equality of Germany, where “little by little the fertile seed of Bismarck’s Prussian patriotism grew into a German semi-democratic nationalism.” Its great virtue was organization: “In every direction,” he wrote, “German activity was organized and was placed under skilled professional leadership, while . . . each of these special lines of work was subordinated to its particular place in a comprehensive scheme of national economy. The upshot increased security, happiness and opportunity for development for the whole German people.”