By Peter Berkowitz

The controversies raging

about the merits of two very different Obama administration policies,

the Affordable Care Act and addressing Iran’s nuclear program, shed

light on the common political outlook that underlies them.

President Obama’s signature domestic initiative and his grandest

foreign affairs undertaking alike reflect a defining feature of the

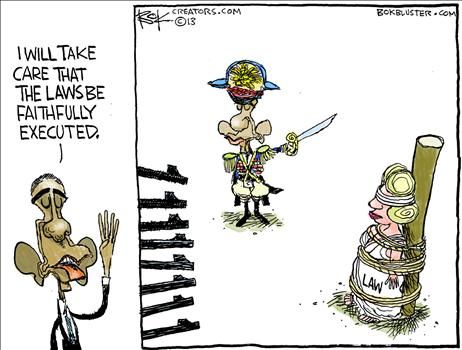

progressive or left-liberal mind. Both betray an incoherent opinion, or

rather incoherent set of opinions, about politics and law. In both

cases, Obama began by exaggerating the primacy of the rule of law.

Subsequently, without fanfare, apology, or apparent regret he blithely

disregarded the requirements of law.

It’s not unheard-of for a politician to change his tune to suit

changing circumstances -- nor should it be. But the left-liberal

tendency to exalt the supreme importance of the rule of law and then to

nonchalantly set it aside when it is no longer expedient reflects

something more than improvised adjustment to the needs of the moment.

This attraction to the extremes is fueled by the same deep-rooted

source.

The left-liberal mindset endemic on the college faculties and law

schools where Barack Obama’s political sensibilities were forged holds

that morals and politics are subject to a universal reason to which the

left-liberal sensibility is uniquely attuned. This conceit receives

expression in a faith that the left-liberal brain trust can embody

complex public policy in general rules and regulations, which can then

be administered smoothly by well-educated bureaucrats and adjudicated

impartially by empathetic judges.

At the same time, the left-liberal mind rebels against established

authorities, hierarchies, and formalities that constrain its ability to

pursue the people’s good and social justice -- at least as it

understands them.

Often enough, this rebellion turns against laws duly enacted by

left-liberals themselves. Obamacare and the Iran nuclear deal are now

demonstrating the destabilizing consequences of governing in accordance

with a love-hate relationship toward the law.

The Affordable Care Act was grounded in enormous confidence in the

power of law -- to redistribute wealth, bring health care to those who

lacked it, improve the quality of insurance of those who already

possessed it and, in the process, remake one-sixth of the nation’s

economy by putting it under tight government management.

The Affordable Care Act itself weighed in at around 2,700 pages. The

regulations implementing it exceed 20,000 pages. Such was the confidence

in the capacity of the transformative power of law that all this was

undertaken by the Obama administration despite the opposition of all

congressional Republicans, who represented a large legislative minority,

and the opposition of a majority of the nationwide electorate.

More than three years after he signed the Affordable Care Act into

law, as he began to grasp that its implementation was foundering, the

president took a step without any basis in law. Last summer, just before

Independence Day, Obama announced that he would suspend for a year the

ACA’s employer mandate, which requires businesses with 50 or more

full-time employees to provide health insurance that conforms to new,

exacting standards.

In taking this extraordinary step, the president certainly did not

claim that he’d decided the duly enacted employer mandate was

unconstitutional after all. Nor did he ask Congress, the lawmaking

branch of the federal government, to change the law. Indeed, he promised

to veto any such bill. He just acted by fiat.

Four months later, in mid-November, in the face of widespread popular

discontent, Obama announced that he would allow insurance companies for

a year to continue to sell insurance policies that violated ACA

requirements. Again, he did not claim that the minimum insurance

standards required by Obamacare’s statutory language and the regulations

his administration had promulgated were illegal, unconstitutional, or

even ill-considered. And again, he rejected out of hand proposed

legislation that would put outlawed insurance policies back in

compliance. Instead, the president gave the insurance companies his

blessing to engage in an illegal activity for a year.

The same inclination to exalt law combined with a penchant for peremptory lawlessness is visible in the Iran deal.

From the beginning, the administration has insisted on the cardinal

importance of American observance of international law, most especially

when dealing with Iran’s nuclear program.

As it happens, international law regarding Iran is clear. In 2006,

the United Nations Security Council passed Resolution 1696, which

“Demands … that Iran shall suspend all enrichment-related and

reprocessing activities, including research and development, to be

verified by the IAEA.” Since then, the Security Council has passed five

more resolutions, most recently in June 2010, reaffirming Iran’s

obligation to halt all enrichment-related and reprocessing activities.

Under international law and the U.N. Charter, the United States has

no legal authority outside of the formal framework of the Security

Council -- either unilaterally or in cooperation with the P5+1 (the

United States, the other four permanent members of the council, and

Germany) -- to set aside these duly enacted resolutions demanding a halt

to all of Iran’s enrichment-related and reprocessing activities.

Article 25 of the U.N. Charter provides that “The Members of the

United Nations agree to accept and carry out the decisions of the

Security Council in accordance with the present Charter.” Among other

things, this core requirement of international law enables third

countries -- supporters as well as opponents of Security Council

decisions -- to form expectations and make plans based on the assumption

that once the council has adopted a decision in accordance with

established procedures, that decision cannot be undone except through

those procedures.

Yet last week the Obama administration signed an interim deal that

legitimizes Iran’s continued enrichment activities, in contradiction to

Security Council resolutions. According to the agreement, while Iran

must cease enriching uranium to 20 percent levels, Tehran may proceed

with uranium enrichment up to 5 percent levels.

In addition, while the interim agreement prohibits Iran from

operating its heavy-water production plant at Arak, which can be used to

produce plutonium for nuclear weapons, the agreement permits Iran, in

violation of U.N. resolutions, to proceed with the plant’s construction.

One can argue in his defense that the president is riding roughshod

over international law in pursuit of a “comprehensive solution” to

Iran’s nuclear program abroad and that his legislative shortcuts when

dealing with health care policy at home are being carried out in pursuit

of a noble goal: affordable health care for all Americans. With regard

to both issues, Obama’s supporters claim -- and the president himself

says -- that his practical approach to problem-solving is proof positive

that he is not by nature an ideological person.

But Obama’s apparent appeal to pragmatism disguises his oscillation

between extremes. One moment he is ideologically driven to use fealty to

the rule of law to overcome the normal (if sometimes morally suspect)

give-and-take -- the horse-trading, glad-handing, and compromise --

necessary for the effective practice of politics. Yet the next moment,

he is ideologically driven to disdain legal process and the constraints

of law.

The worthy alternative to the left-liberal sensibility is not one

that is opposed to the universal claims of reason but rather one that

involves a more judicious interpretation of reason. It holds, among

other things, that it is unreasonable to attempt to make public policy

decisions on the basis of abstract theories. It also emphasizes the

wisdom of experience, and accords latitude to the exercise of practical

judgment in balancing competing interests, opinions, and principles. It

holds that government must be limited to secure the rights shared

equally by all. And it holds that appreciating the limits of law is

crucial to vindicating the majesty of the law.

You could call this way of thinking conservative. It was brilliantly

displayed and eloquently defended in the speeches and writings of

18th-century British statesman Edmund Burke, the father of modern

conservatism.

What is urgent, though, is to appreciate the stake that both left and

right have in this more reasonable interpretation of reason and law,

which is indispensable to the preservation of liberty at home and to the

defense of the nation abroad.

Peter Berkowitz is a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution, Stanford University. His writings are posted at www.PeterBerkowitz.com.

No comments:

Post a Comment