Some things even the Obama brain trust doesn’t want credit for.

There aren’t too many takers for that claim. In a Bloomberg poll, only 36 percent of Americans approve of Obama’s efforts to create jobs. New York Times reporter Jennifer Steinhauer claims without providing any examples that some congressional Democrats “oppose the bill simply for its mental connection to the stimulus bill.” Also in America’s newspaper of record, Nobel Laureate Paul Krugman, a prominent voice in favor of Keynesian economic intervention, argues that the ARRA stimulus failed because it was not large enough to close a gap in aggregate demand brought on by a spike in the personal savings rate.

But one key goal of the stimulus was achieved almost a year ago.

That’s the provocative but apparently accurate claim of Robert Higgs in a recent Independent.org post. Rebuking the mainstream economic belief that unemployment is high and growth stagnant because consumers are not spending, Higgs demonstrates that personal consumption expenditures in fact recovered to their pre-recession levels by the last quarter of 2010. Higgs, the Independent Institute's senior fellow in political economy and editor of The Independent Review, writes:

According to [table 2.3.3 in this Department of Commerce database], real personal consumption expenditure recovered from its recession decline by the fourth quarter of 2010. Continuing to grow, it now stands (as of the most recent data, for the second quarter of 2011) even farther above its pre-recession peak.

Real government expenditure for consumption and investment (this concept does not include the government’s transfer spending, such as unemployment insurance benefits and social security benefits) is also running higher than its pre-recession level. In the second quarter of 2011, it was running more than 2 percent higher (recall that this is “real,” or inflation-adjusted spending; nominal spending has grown substantially more).

How can an economy continue to stagnate after the gap in aggregate demand has been closed? Taking up the slack in demand is supposed to be the heavy lifting of an economic recovery, the part of the job so big only the government can do it.

Demand-deslackification is considered so central to a recovery that it can justify drafting the young to fight in horrible wars, just to reduce the surplus labor supply. Despite important work by former Obama brain trustee Christina Romer and others, the myth that World War II ended the Great Depression persists. Recently, in the process of losing a CNN exchange with economist Kenneth Rogoff, Krugman did himself no credit by arguing that if the public could be hoodwinked into increasing inflation and deficit spending to prepare for a hoax invasion by space aliens, “this slump would be over in 18 months.”

With or without E.T.’s help, the recession ended more than 18 months ago. According to National Bureau of Economic Research, the trough occurred in June 2009. More important, Keynesian “equilibrium” was achieved last Christmas.

Yet month after month the Bureau of Labor Statistics reports unemployment above 9 percent, higher than it was when the ARRA stimulus became law.

“There’s really nothing in Keynesian theory that encompasses indebtedness—consumer indebtedness and corporate indebtedness. That’s why these guys are at sea. This boom was built on heavy leverage. People are looking back, and they’re saying, ‘We were crazy to go that deeply into debt. We have to change that.’”

- Robert Higgs

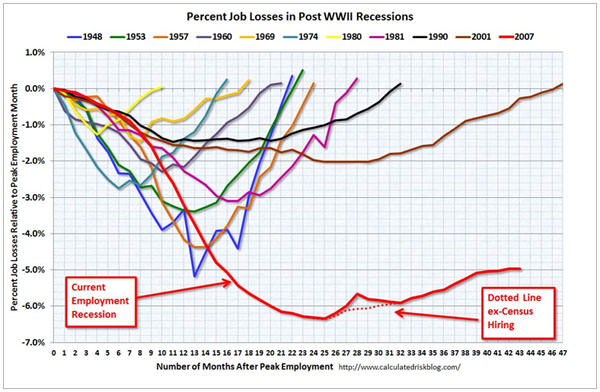

Even allowing for a conventional lag in post-recession job growth, the jobs recovery is by far the most anemic since the end of World War II. At the Calculated Risk blog, Bill McBride maintains a handy chart comparing peak-trough-peak employment drops and recoveries for every recession since 1948. The pace of hiring that has held for the last two years would not mitigate job losses from the current recession until around 2018:

This grim trend helps explain the rage and frustration of Krugman and other Keynesians who blame even ARRA for being too small and promote the concept of the “liquidity trap” to explain why expanding the money supply has not had the effect of creating a new economic bubble. Don’t be fooled by their irreducible uncertainty.

From the Keynesian perspective, all the problems have been solved. Demand has been restored. A strong dollar and a threatened increase in the net savings rate have been, with vast and concerted public effort, averted. Interest rates are low or effectively negative. Deficit spending has more than doubled. And yet the economy stays narcotized.

“There’s really nothing in Keynesian theory that encompasses indebtedness—consumer indebtedness and corporate indebtedness,” Higgs said in a phone interview. “That’s why these guys are at sea. This boom was built on heavy leverage. People are looking back, and they’re saying, ‘We were crazy to go that deeply into debt. We have to change that.’”

In Higgs’ view, the trillions of new dollars that have been created are being absorbed into critically ill balance sheets. “Firms, if they have cash flow, are repaying debt,” he said. “If they increase output they’re doing it with their existing workforce, maybe augmented by new equipment or software.”

There is evidence for that view in BEA statistics on gross savings, but Higgs cautions against over-reliance on central databases. “You can’t look at things sensibly at the macro level,” he says. “You have to look at things in different sectors and regions.”

The Federal Reserve is expected to consider another blunt weapon of macroeconomics—more quantitative easing—at next week’s Open Market Committee confab. The Fed may try to mitigate QE3 by selling short-term debt while buying long-term debt. That stunt carries risks of its own. Combined with the Fed’s “interest on reserves” program and other innovations, it also renders Fed strategy far more opaque than it was even in the Greenspan era, when you could get by just keeping track of the Fed Funds rate.

Opacity is a genuine problem for people who need to know what their money will be worth but are too busy making payroll or avoiding insolvency to devote hours to studious Bernankeology. Not to mention employers who, through the scrim of “stimulative” finagling with tax rates and lack of clarity around costs from the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, don’t know how much any new employee is going to cost.

You can’t really solve these problems, but there is one simple method that works whether you’re selling a house, an idea, or your own skills: Lower your asking price. Wages and prices need to fall. Unfortunately, Keynesians only know how to prevent that from happening.

Tim Cavanaugh is a senior editor at Reason magazine.

No comments:

Post a Comment