Diplomacy is the US president’s preferred weapon. Now he must prove he can wield it

By Edward Luce, Financial Times

In

the dying days of the Soviet Union, President George H W Bush gave a

speech in Kiev urging Ukrainian nationalists not to provoke Moscow. US

conservatives dubbed it his “chicken Kiev” speech. Having long since

been branded America’s appeaser-in-chief, President Barack Obama

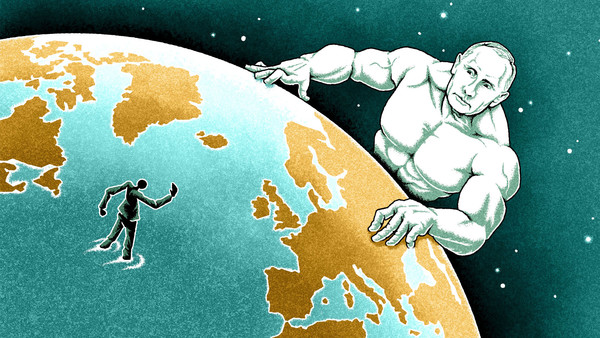

now confronts his own chicken Kiev moment. Can Mr Obama stand up to

Vladimir Putin, the Russian fox circling the chicken coop? It is unclear

whether he has the will and the skill – let alone the means – to do so.

Yet the future of his presidency depends on it. There can be little

doubt that Mr Putin wants to restore the boundaries of the Russian

empire. Mr Obama must somehow find a way to frustrate him.

It will require a very different Mr Obama from the semi-detached one

the world has grown used to. Even before Mr Obama became president,

critics accused him of appeasing a revanchist Russia. John McCain, his

Republican opponent, seized on Russia’s semi-invasion of Georgia in 2008

as an example of where he would draw the line against Moscow’s

expansionist creep. Mr Obama’s unwillingness to match his opponent’s

hawkishness chimed far better with the US public mood. Americans were

tired of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and Mr Obama promised to end

them. He has done so.

If anything, Americans are even warier of entanglements today. Yet

Russia’s occupation of the Crimea dramatically changes the landscape.

Everything that Mr Obama wants – nation building at home, a nuclear deal

with Iran, a quiescent Middle East and the pivot to Asia – hinges on

how he responds to Mr Putin. At the start of his presidency, Mr Obama

offered to “reset” US-Russia relations. That is now in tatters. Along

with many others, Mr Obama has consistently underestimated Mr Putin’s

readiness to challenge the status quo. As recently as last Thursday, the

White House dismissed predictions of a Russian incursion into Crimea.

In a 90-minute phone call on Saturday, Mr Putin hinted to Mr Obama he

was prepared to extend Russia’s Crimean occupation into eastern Ukraine.

It would be naive to assume he will not.

What can Mr Obama do to prevent it? His starting point must be to

ignore the chicken hawks in Washington. Threatening a military response –

as Mr Obama’s most trenchant critics are now urging – would be

manifestly absurd. There is no US military solution to the crisis.

Drawing a “red line” between Crimea and the rest of Ukraine, or between

its eastern and western halves, would merely invite Moscow to call

Washington’s bluff. Besides, Mr Obama’s record on red lines is a poor

one. The last one he drew was in Syria,

where he promised to intervene if Bashar al-Assad’s regime used

chemical weapons on his people. Mr Assad repeatedly called Mr Obama’s

bluff last summer. Ironically, it was Mr Putin who saved the US

president from the consequences of his own rhetoric – and a humiliating

rebuff on Capitol Hill – by persuading Syria’s dictator to agree to

dismantle his chemical stockpile. That now looks to be a dead letter. In

retrospect it would have been better if Mr Obama had ordered air

strikes on Syria without consulting anyone. In any case, red lines will

only embolden Mr Putin.

Everything Obama wants – nation building at home, a nuclear deal with Iran, a quiescent Middle East – hinges on how he responds to Putin

Which leaves diplomacy. Mr Obama’s philosophy is based on the

Churchillian line that “jaw jaw” is better than “war war”. The approach

is good. But his execution has been middling at best. Too often, Mr

Obama’s stance has been to say the right thing but with little follow-

through. Just ask the people of Egypt, who remain confused about whether

Mr Obama supports democracy or not. His administration has three

policies on Egypt

– the Pentagon, which wants to maintain US-Egypt ties come what may;

the Department of State under John Kerry, which backed last year’s coup

against the Muslim Brotherhood; and the White House, which condemned the

coup but has left day-to-day decisions to the first two. On Egypt, Mr

Obama has been absent even inside Washington. He has left much the same

impression on Syria, which is now rolling back last year’s

Putin-brokered deal, and in Afghanistan, where Hamid Karzai is trashing

Mr Obama’s hopes of a treaty that would leave US forces in place.

Diplomacy is Mr Obama’s preferred weapon. Now he must prove that he

knows how to wield it. The Washington debate in the past 48 hours has

posed a false choice between setting a red line and doing nothing. But

there is plenty Mr Obama can do in between. Rallying America’s allies to

the side of Ukraine’s shaky government is obviously one. That must

include large pledges of cash. Reassuring America’s eastern European

allies that their sovereignty will be protected is another. This could

include restoring the missile defence systems Mr Obama scrapped in the

days of the “reset”. He could also accelerate plans to export US natural

gas and oil to Europe to counter Moscow’s energy stranglehold.

Above all, Mr Obama needs to convince Mr Putin that he will not be

outfoxed. That means summoning a determination he has too often lacked.

It will mean taking risks without being reckless. In 1991, Bush senior

flew to Kiev to warn Ukrainians against “suicidal nationalism”. Mr Obama

must warn Mr Putin against embarking on a course of suicidal

imperialism. In spite of everything, he remains the right person to

deliver that message. Kiev would be the perfect venue to deliver it.

Related Reading:

No comments:

Post a Comment