The claim that last month’s democratic revolution in Ukraine

was actually driven by ultra-right extremists, fascists, or even

“neo-Nazis” has been a staple of Kremlin propaganda. It is also echoed

by Western pundits who think that Vladimir Putin is getting a bum rap and the United States is backing the bad guys in this conflict. It is true that far-right nationalists are a troubling, though by no means dominant, presence on Ukraine’s

political scene and a potential problem for the new leadership’s quest

for European integration. But the cries of “fascism” from Moscow and its

apologists are breathtakingly hypocritical, considering the Putin

regime’s entanglement with far-right, ultranationalist and, yes, fascist

elements at home and abroad.

It’s hard to gauge the actual extent of extremist involvement in the

Maidan protests, which began in late November in response to

Yanukovych’s rejection of a European Union trade deal. At the start of

February, Dmitry Likhachev, a Russian Jewish journalist and board member of the Euro-Asian Jewish Congress, estimated

that “radical nationalists” made up about one percent of the

protesters. On one occasion in the early days of the “Euromaidan,” a

notorious hatemonger, poet Diana Kamlyuk, took advantage of an open

microphone night to make overtly racist and anti-Semitic remarks; but

Likhachev stressed that this was an isolated, widely condemned incident,

and that the rallies featured prominent Jewish speakers as well as

Jewish religious and cultural events.

As tensions between protesters and riot police escalated, the

radicals took on a larger role—particularly Right Sector, a paramilitary

group some view as bordering on neo-Nazism because of its admiration

for World War II-era Ukrainian nationalist, onetime Nazi collaborator Stepan Bandera. (While Bandera’s record on anti-Semitism is a matter of some dispute,

his followers unquestionably committed atrocities toward Poles,

Russians, Jews, and others; by any objective reckoning, he was certainly

more terrorist than freedom fighter.) Right Sector has made some effort

to improve its image: its leader, Dmitro Yarosh, has met with the Israeli ambassador in Kiev to assure him that the group strongly opposes anti-Semitism and xenophobia. Yarosh and other militants have also praised Jewish fighters on the Maidan. Still, concerns about their influence justifiably remain.

Another alarming factor is the nationalist party Svoboda (“Freedom”), whose head, 45-year-old Oleg Tyahnibok, has a history of anti-Semitic and racist comments—though he has tried to reinvent

himself as a moderate. Svoboda has about 8 percent of the seats in

Ukraine’s parliament; thanks to the deal brokered by Germany and France before Yanukovych’s resignation, it also holds four of the twenty posts in the interim government,

including that of Minister of Defense. The party’s attempts to shed its

thuggish reputation have not been entirely successful; on March 18,

three Svoboda parliament members threatened and assaulted

the chief of Ukraine’s TV Channel 1, angered by what they regarded as

the station’s pro-Russian slant, and forced him to write a statement of

resignation. The incident, which caused near-universal outrage, is now

being investigated.

The good news, as historian Timothy Snyder points out

in The New Republic, is that current polls show Svoboda getting 2 or 3

percent of the vote in May’s presidential election. And some reports on

the right-wing menace in Ukraine clearly overstate the party’s impact.

Thus, a March 13 column in the Los Angeles Times and a March 18 Foreign Policy article

pointed to Svoboda’s successful push for a law making Ukrainian the

country’s sole official language—without mentioning that Interim

President Oleksandr Turchynov later vetoed the bill.

Meanwhile, in Russia, nationalists in the upper echelons of power

include such prominent figures as former NATO envoy and current Deputy

Prime Minister Dmitry Rogozin, who first entered the political scene as a

leader of the nationalist bloc Rodina (Motherland). In 2005, Rodina was

banned from Moscow City Council elections for running a blatantly

racist campaign ad:

the clip showed three Azerbaijani migrants littering and insulting a

Russian woman and Rogozin stepping in to tell them off, and ended with a

slogan promising to “clean up the trash.” While Rogozin is no fan of

America, he has some peculiar American fans: in 2011, a glowing tribute

that concluded with, “Let’s hope that Rogozin rises to power in

Russia—and for the rise of a ‘Rogozin’ in America and elsewhere

throughout the West,” appeared on the “white identity” website,

Occidental Observer.

Rodina co-founder and Rogozin’s erstwhile rival for its leadership,

Sergei Glazyev, most recently served as Putin’s man in charge of

developing the Customs Union—the alliance with Kazakhstan and Belarus

that was also to include Ukraine. Like Rogozin, Glazyev has attracted

the sympathetic attention of far-right kooks in the Unites States—in

this case, Lyndon LaRouche: in 1999, LaRouche Books published an English

translation of Glazyev’s book, “Genocide: Russia and the New World Order,” with a foreword by LaRouche himself.

But Rogozin and Glazyev are mere peons compared to self-style

“traditionalist” intellectual Alexander Dugin, a writer and professor at

Moscow State University. In his New Republic article, Snyder identifies

Dugin—“an actual fascist”—as “the founder of the Eurasian movement,”

the ideology that provides the foundation for Russia’s expansion into

Ukraine.

In fact, Dugin—who, in his writings in the 1990s, was quite explicit

about the fascist and even Nazi roots of his views, asserting that true

fascism had never been tried and would be born in Russia—is more than

just the father of an idea. As documented in a 2009 article by Ukrainian scholar Andreas Umland (who has also chronicled

the rise of extremism in Ukraine), Dugin has extensive, close ties to

Russia’s political elites and the pro-Kremlin media. A number of

high-level officials and journalists have served on the leadership

council of his organization, the International Eurasian Movement.

Dugin’s admirers include Ivan Demidov, a TV producer who at one point,

in 2008, headed the ideology section of the ruling party, United Russia.

Dugin’s frightening rhetoric has been on display in recent days.

After a massive antiwar demonstration in Moscow on March 15, he wrote on

his Facebook page,

“This is no longer simply filth, ideological opponents, or dissenters,

but a parade of traitors. Today, they have risen against the Russian

people, against our State, against our history. They are defending

murderers, occupiers, Nazis, and NATO. All the participants in this

march of the fifth column have been condemned—by history, by the people,

by us.” Then, he quoted a line from a famous wartime poem: “As many

times as you see them, kill them.” (The poem, of course, referred to

German invaders.)

If those are the ideologues, it’s hardly surprising that some of

Russia’s foot soldiers in the conflict with Ukraine are of the

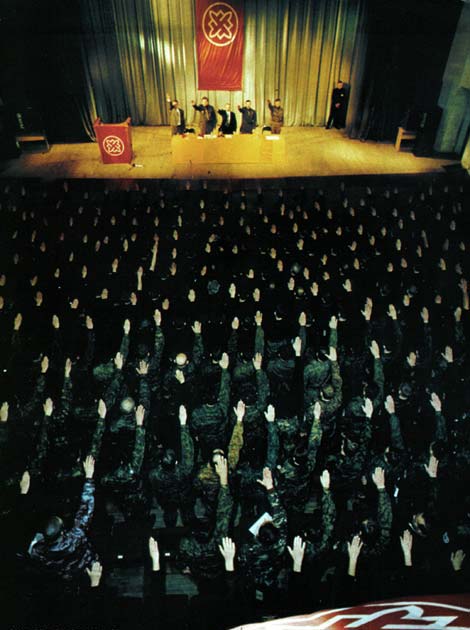

brownshirt type. Most notable among these is Pavel Gubarev, the

pro-Russian activist in Donetsk who briefly proclaimed

himself the city’s “People’s Governor” and raised a Russian flag over

the local government building. A few days after Gubarev gained

notoriety, it was revealed that he had once been an activist in the

militant group Russian National Unity, whose emblem bears an

unmistakable resemblance to the swastika. (Photos

of Gubarev in uniform made the rounds of the Internet):

And, shortly

before the March 16 referendum, the Kremlin’s man in Crimea, Sergei

Aksyonov, used a blatant anti-Semitic code in a televised speech,

referring to Ukraine’s new leadership as “an unnatural union of

cosmopolite oligarchs who have grown rich plundering the Soviet era’s

heritage, and neo-Nazis.” Of course, “cosmopolite” was once an infamous

Soviet euphemism for “Jew”—and it is no accident that the best-known

business oligarch allied with the new government is a Jewish man, Ihor

Kolomoysky.

Then there’s the matter of the “international observers” Moscow invited to the referendum in Crimea—a veritable freak central

of neo-Stalinists and far rightists including Belgian neo-Nazi Luc

Michel, Hungarian right-wing extremist Bela Kovacs, and Serbian-born

American paleocon and war crime apologist

Srđa (Serge) Trifković. Another observer, Polish parliament member

Mateusz Piskorski, who praised the referendum in a Russia Today

interview, is a former neo-Nazi in a very literal sense. In the late

1990s and early 2000s, Piskorski published a magazine called Odala,

which openly praised Nazi Germany, interviewed Holocaust deniers, and

proclaimed that “considering the decay and multi-racialism of the West,”

a united Slavic empire was “the only hope for the White Race.”

Piskorski now belongs to Dugin’s Eurasian Movement.

Umland’s 2009 article on Dugin and creeping Russian fascism ended with the eerie prediction: “Should Dugin and his followers succeed in further extending their reach into Russian high politics and society at large, a new Cold War will be the least that the West should expect from Russia, during the coming years.” Perhaps fascism has indeed won—and not in Ukraine.

Mo, you use to open your every posts with a song, a video a master piece of humor and comedy...What happened?

ReplyDeletehttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2tMKO_9SD1Y

Did this mortal world got the best of you?? You can feel again... Happy Sabbath and Daniels' Spring, dear soul... welcome back...

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2tMKO_9SD1Y