Along with the lower standards of rational basis review and exacting or intermediate scrutiny, strict scrutiny is part of a hierarchy of standards employed by courts to weigh an asserted government interest against a constitutional right or principle that conflicts with the manner in which the interest is being pursued, United States v. Carolene Products Company, 304 U.S. 144 (1938). Strict scrutiny is applied based on the constitutional conflict at issue, regardless of whether a law or action of the Federal government, a state government, or a local municipality is at issue. For a law or code restricting speech to survive strict scrutiny and be upheld as constitutional it must be 1) narrowly-tailored, 2) the state must also have a compelling governmental interest, and 3) the law or policy must be the least restrictive means for achieving that interest.

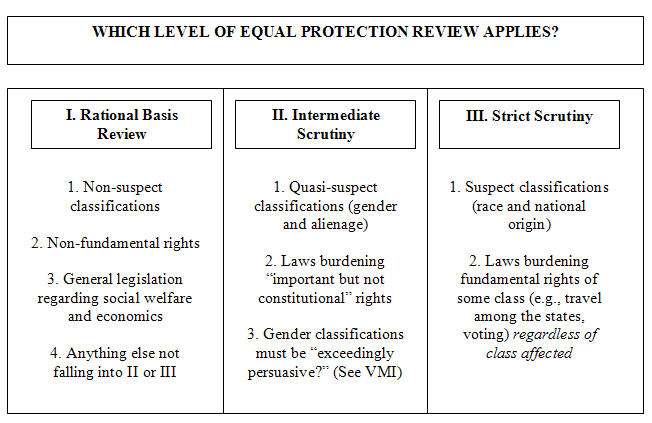

Strict scrutiny arises in two basic contexts: when a "fundamental" constitutional right is infringed, particularly those listed in the Bill of Rights and those the Court has deemed to be a fundamental right protected by the "liberty" or "due process" clause of the Fourteenth Amendment; or when the government action involves the use of a "suspect classification" such as race or, sometimes, national origin that may render it void under the Equal Protection Clause. See Carolene, supra, at FN4.

Let's take each of the prongs and consider them in greater detail:

FIRSTLY, any restriction must be justified by a compelling governmental interest. While the Court has never brightly defined how to determine if an interest is compelling, the concept generally refers to something necessary or crucial, as opposed to something merely preferred. Examples include national security, preserving the lives of multiple individuals, and not violating explicit constitutional protections. For an idea of what constitutes a bright-line test, see Miranda v. Arizona 384 U.S. 436 (1966), Goldberg v. Kelly, 397 U.S. 254 (1970), S.E.C. v. Chernery Corporation, 332 U.S. 194 (1947), Heckler v. Campbell, 461 U.S. 458 (1983), Bowen v. Georgetown University Hospital, 488 U.S. 204 (1988), Sameena, Inc. v. U.S. Air Force, 147 F.3d 1148 9th Cir. (1998).

SECONDLY, the law or policy must be narrowly tailored to achieve that goal or interest. If the government action encompasses too much (Overbreadth Doctrine) or fails to address essential aspects of the compelling interest (Under-Inclusive Doctrine), then the rule is not considered narrowly tailored.

Overbreadth Doctrine. A statute doing so is overly broad if, in proscribing unprotected speech, it also proscribes protected speech. Overbreadth is closely related to vagueness; if a prohibition is expressed in a way that is too unclear for a person to reasonably know whether or not their conduct falls within the law, then to avoid the risk of legal consequences they often stay far away from anything that could possibly fit the uncertain wording of the law. The law's effects are thereby far broader than intended or than the Constitution permits, and hence the law is overbroad. The esteemed constitutional scholar, Lewis Sargentich, first analysed and named the doctrine in his famous note in the Harvard Law Review, The First Amendment Overbreadth Doctrine (83 Harv. L. Rev. 844). Then, citing Sargentich's note, the Court in Broadrick v. Oakland, 413 U.S. 601, explicitly recognized the doctrine in 1973.

Under-Inclusive Doctrine. An under-inclusive law is not necessarily unconstitutional or invalid. The Court has recognised that all laws are under-inclusive and selective to some extent. If a law is substantially under-inclusive, however, it may be unconstitutional. If a law infringes on constitutionally protected free speech, press, or associational rights, it may be unconstitutionally under-inclusive if it is based on the content of the speech or somehow regulates ideas. In R.A.V. v. City of St. Paul, 505 U.S. 377 (1992), the Court struck down a hate speech ordinance that prohibited "the display of a symbol which one knows or has reason to know 'arouses anger, alarm or resentment in others on the basis of race, color, creed, religion or gender.'" A youth in St. Paul, Minnesota, had been prosecuted under the ordinance for burning a cross in the yard of an African-American family. The Court held that the law was unconstitutionally under-inclusive under the First Amendment because it punished only certain speech addressing particular topics; the law addressed the content, rather than the manner, of the speech.

A law is not necessarily invalid just because it is under-inclusive. For example, a statute that prohibited the use of loudspeaker systems near a hospital might be under-inclusive for failing to prohibit shouting or the use of car horns in the same area. This type of under-inclusiveness concerns only the manner of delivering speech, however, and is therefore more likely to pass constitutional scrutiny than a statute that prohibits speech on particular subjects.

THIRDLY AND FINALLY, the law or policy must be the least restrictive means for achieving that interest. More accurately, there cannot be a less restrictive way to effectively achieve the compelling government interest, but the test will not fail just because there is another method that is equally the least restrictive. Some legal scholars consider this 'least restrictive means' requirement part of being narrowly tailored, though the Court generally evaluates it as a separate prong. The "least restrictive means," or "less drastic means," test is a standard imposed by the courts when considering the validity of legislation that touches upon constitutional interests. If the government enacts a law that restricts a fundamental personal liberty, it must employ the least restrictive measures possible to achieve its goal. This test applies even when the government has a legitimate purpose in adopting the particular law. The "Least Restrictive Means Test" has been applied primarily to the regulation of speech. It can also be applied to other types of regulations, such as legislation affecting interstate commerce.

In Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U.S. 479 (1960), the Court applied the least restrictive means test to an Arkansas statute that required teachers to file annually an Affidavit listing all the organisations to which they belonged and the amount of money they had contributed to each organisation in the previous five years. B. T. Shelton was one of a group of teachers who refused to file the affidavit and who, as a result, did not have their teaching contract renewed. Upon reviewing the statute, the Court found that the state had a legitimate interest in investigating the fitness and competence of its teachers, and that the information requested in the affidavit could help the state in that investigation; however, according to the Court, the statute went far beyond its legitimate purpose because it required information that bore no relationship to a teacher's occupational fitness. The Court struck down the law because its "unlimited and indiscriminate sweep" went well beyond the state's legitimate interest in the qualifications of its teachers.

Two constitutional doctrines that are closely related to the least restrictive means test are the Overbreadth Doctrine, supra, and Vagueness Doctrine. These doctrines are applied to statutes and regulations that restrict constitutional rights.

The least restrictive means test, the Overbreadth Doctrine, and the Vagueness Doctrine all help to preserve constitutionally protected speech and behaviour by requiring statutes to be clear and narrowly drawn, and to use the least restrictive means to reach the desired end.

Legal scholars, including judges and professors, often say that strict scrutiny is "strict in theory, fatal in fact," because popular perception is that most laws subject to this standard are struck down. An empirical study of strict scrutiny decisions in the federal courts, however, conducted by Adam Wrinkler found that laws survive strict scrutiny over 30% of the time. In one area of law, religious liberty, laws survived strict scrutiny review in nearly 60% of applications.